I recently found myself wondering how astrophotography actually began. One quiet evening, with a cup of coffee in hand, I went looking for a proper story behind the first images of the night sky. Surprisingly, there wasn’t much to find — just a few short articles, brief mentions of early lunar photos, the Henry brothers, scattered paragraphs here and there. Nothing that truly walked through the beginnings of this art.

So I decided to follow the trail myself. While exploring different sources, I stumbled upon a simple timeline of key moments in astrophotography. It sparked an idea: to rebuild it into something fuller - to expand each date with a bit of context, gather images tied to each milestone, and turn these fragments of history into a clear, gentle path through time.

Nothing too heavy or academic. Just a clean timeline:

Date → Event.

I sifted through old archives, articles, historical notes, astronomy resources and early photographs, gathering everything into one place and translating it along the way. The result is below. If you notice anything that should be corrected, feel free to let me know.

So…

Early Experiments and Inventions

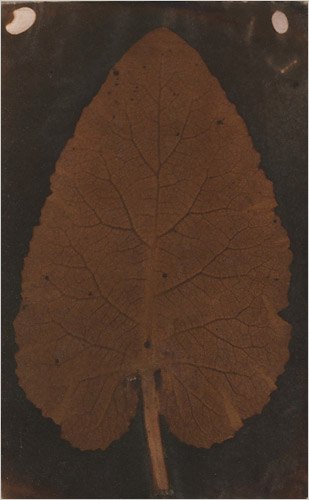

1800

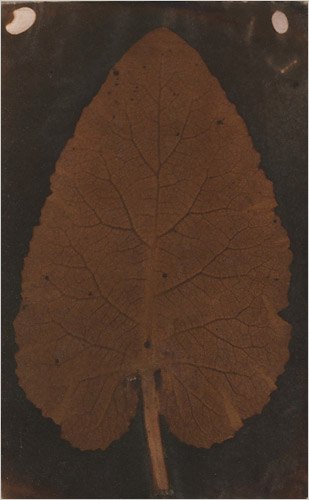

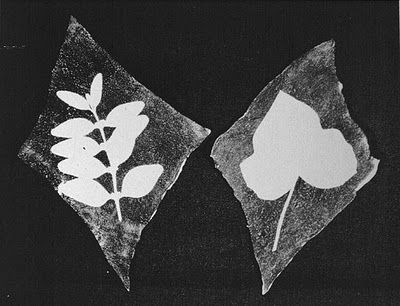

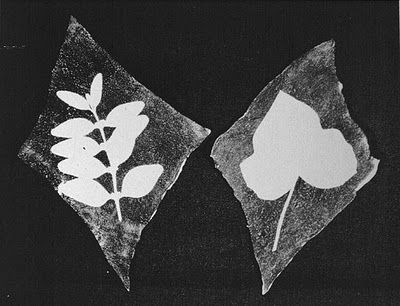

Thomas Wedgwood (1771–1805) develops a method for making “sun pictures” by placing opaque objects on pieces of cowhide treated with silver nitrate. These were among the earliest photographic experiments. They looked something like this:

There were debates in 2008 about whether Wedgwood was actually the author of the first photogram. Before that, William Fox Talbot was credited. The idea that Wedgwood was the true author was later rejected.

Here is Thomas himself. Some historians consider his shadow images to be the first photographs, and call him the first photographer.

1816

1816

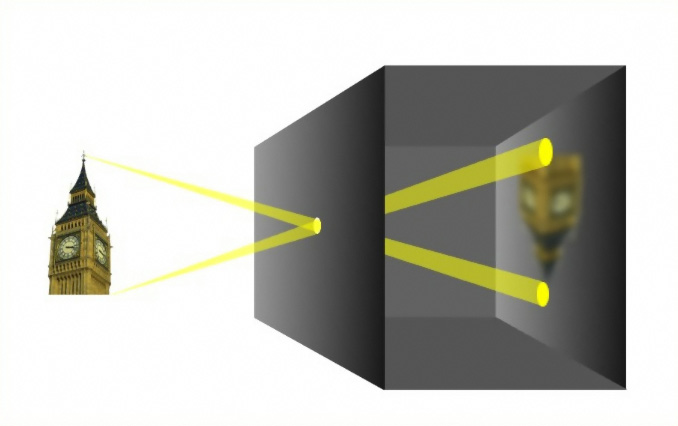

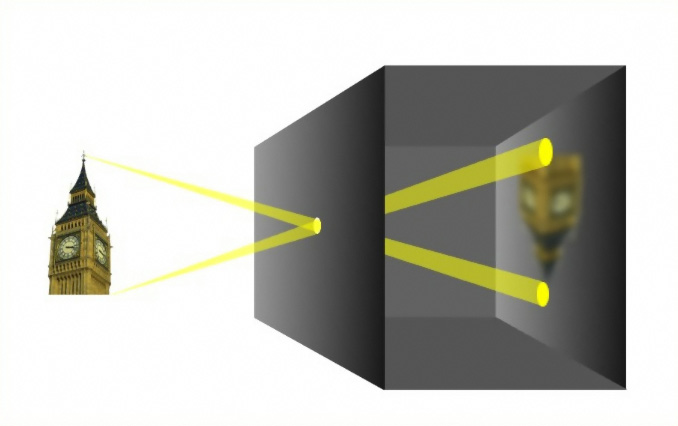

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833) combines a camera obscura with light-sensitive paper. If you haven’t seen a camera obscura before, it looks like this:

It’s a lightproof box with a small opening on one side and a screen (a piece of thin white paper or frosted glass) on the opposite wall.

1825

In 2002, a previously unknown photograph by Niépce was found in a French collection. Researchers discovered that it was made in 1825. The image shows an engraving of a young boy leading a horse into a stable. The photograph was later sold for 450,000 euros at an auction held by the French National Library.

Here it is:

1826

1826

Niépce creates the first permanent image, known as a heliograph, using a camera obscura and a thin layer of bitumen. The photo shows a view from a window overlooking rooftops in Le Gras, France. This image was long considered the oldest surviving photograph until the 2002 discovery mentioned above.

It’s hard to imagine, but the exposure time for this photograph was 8 hours.

By 1829, Niépce was 64 and in poor health. He and his older brother Claude had spent their entire inheritance on inventions, but none of them brought success or financial stability. Heliography became Niépce’s main focus, and he put all his remaining energy into it. He passed away in 1833.

In 1970, the International Astronomical Union named a crater on the far side of the Moon after him.

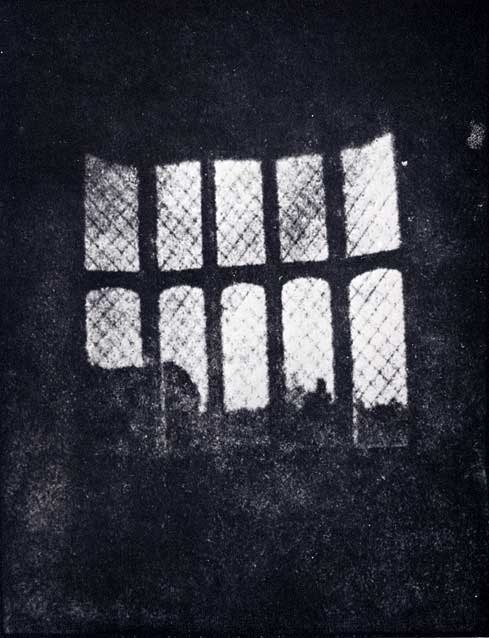

1835

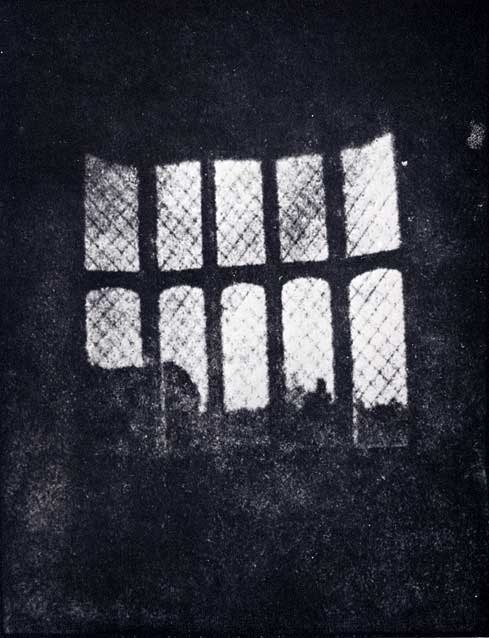

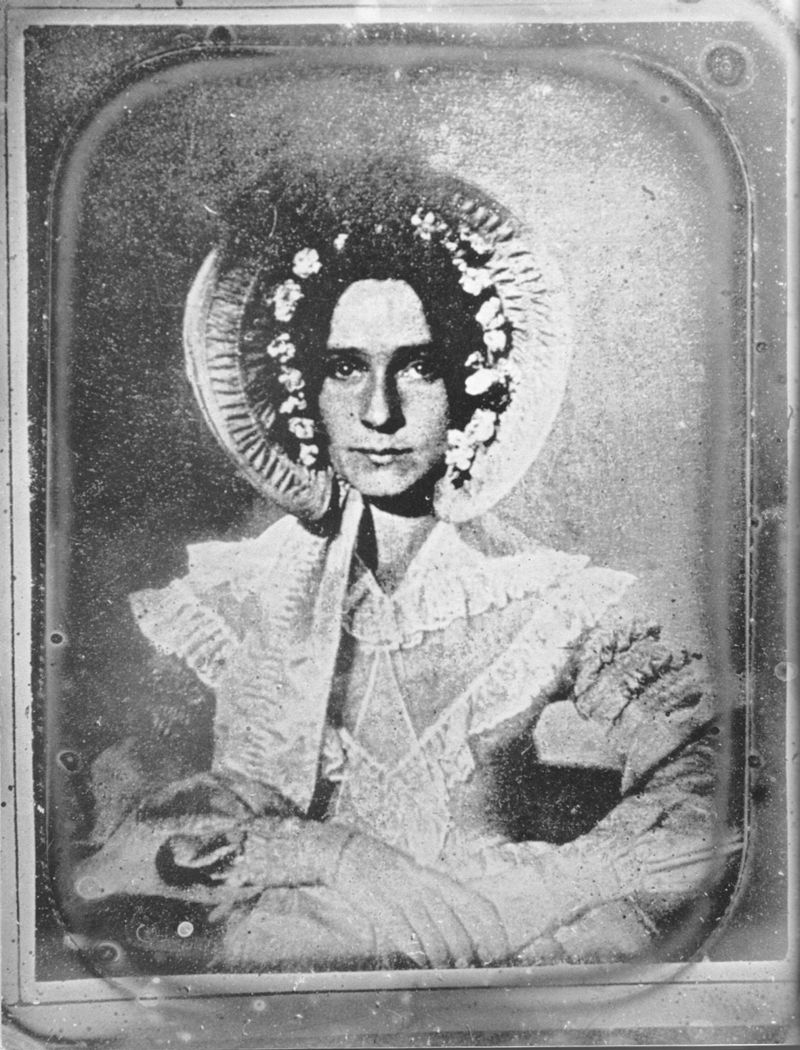

Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877) creates the first photographic negative. As the image medium he used paper soaked in silver nitrate and a salt solution. He photographed the window of his library from the inside using a camera with an optical lens.

This gave photography a huge boost and by 1842 it became possible to create images like this one:

The photo shows Horatia Feilding, Talbot’s half-sister.

In 1976, the International Astronomical Union named a crater on the visible side of the Moon after Talbot.

1837

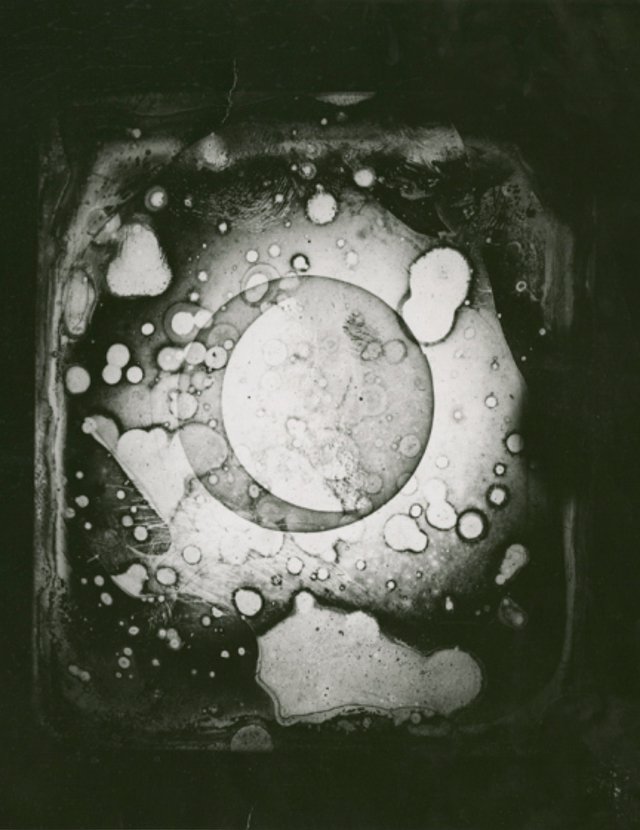

Louis Daguerre creates images on silver-plated copper plates coated with silver iodide and developed with heated mercury vapor. These images became the first examples of the daguerreotype:

1838

1838

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel makes the first scientifically reliable measurement of stellar parallax. He measured the annual parallax of the star 61 Cygni.

Early Astrophotography

1839

François Arago, a French physicist and astronomer, announces the invention of photography. On January 7, 1839, he presented a report on the work of Daguerre and Niépce at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences. He also helped the French government purchase the invention and make the daguerreotype publicly available. Daguerre agreed as long as he and his children received a lifetime pension. During the same presentation, Arago showed Daguerre’s first photograph (The Artist’s Studio, shown above).

Arago also predicted that photography would one day be used in selenography, the branch of astronomy that studies the nature and terrain of the lunar surface.

In 1935, the International Astronomical Union named a crater on the visible side of the Moon after Louis Daguerre.

1839

Daguerre makes the first attempt at a daguerreotype of the Moon. The result was unsuccessful because long exposure times caused severe blurring. There were still 160 years to go before the arrival of the HEQ5 Pro.

1840

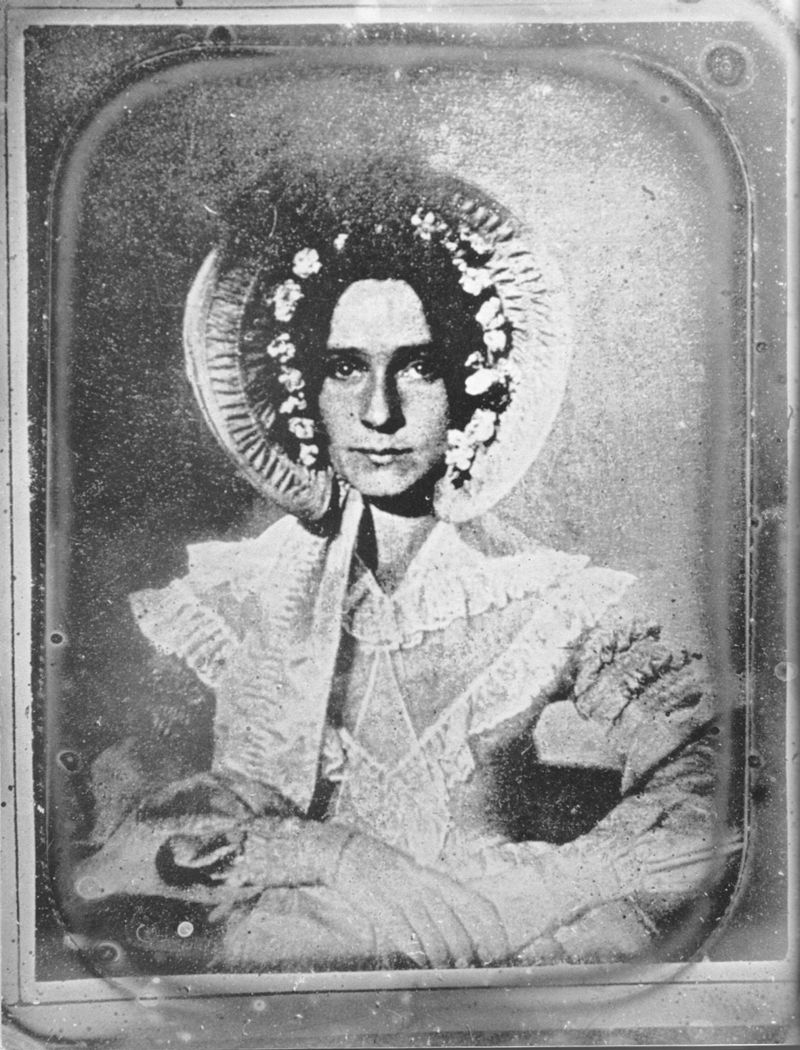

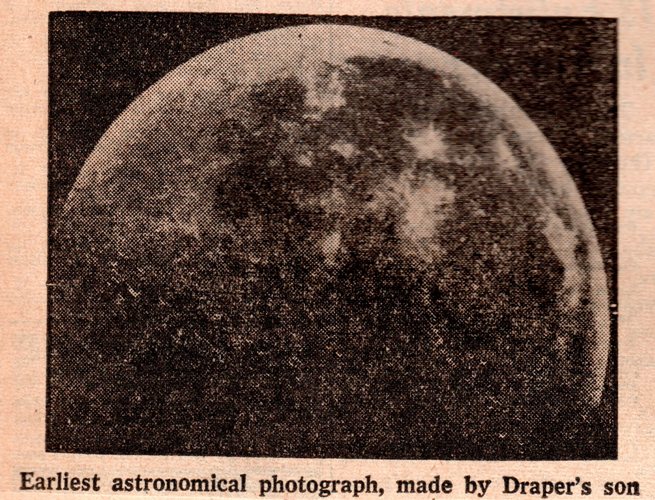

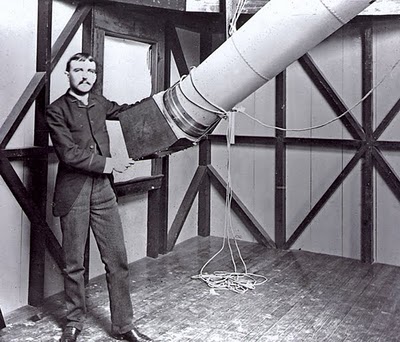

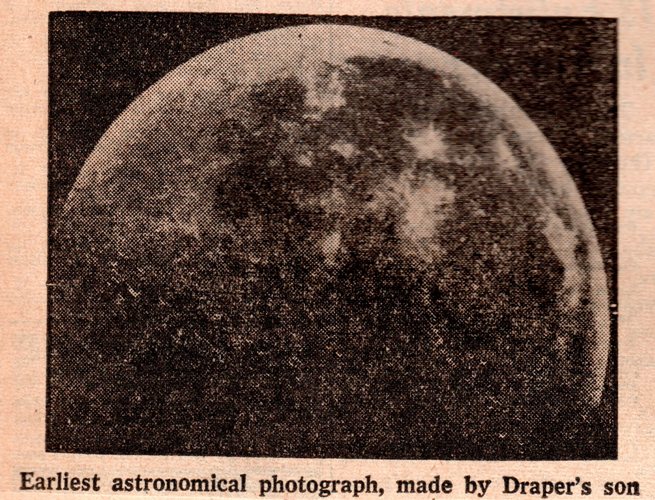

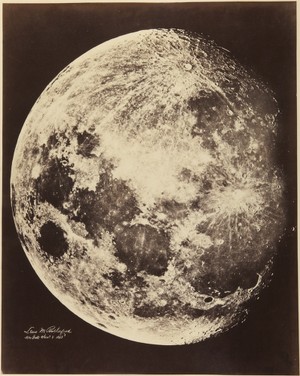

John William Draper (1811–1882) captures the first successful and properly exposed daguerreotype of the Moon. He used a 6-inch reflector with a long focal length and a 20-minute exposure.

This gives us the date of the first photograph of the Moon. Around the same time, Draper also made the

first portrait photograph in history. Just like Henry Talbot, he photographed his sister (funny how none of them photographed their wives).

A scientist, physician, astronomer, philosopher and probably a romantic at heart.

1842

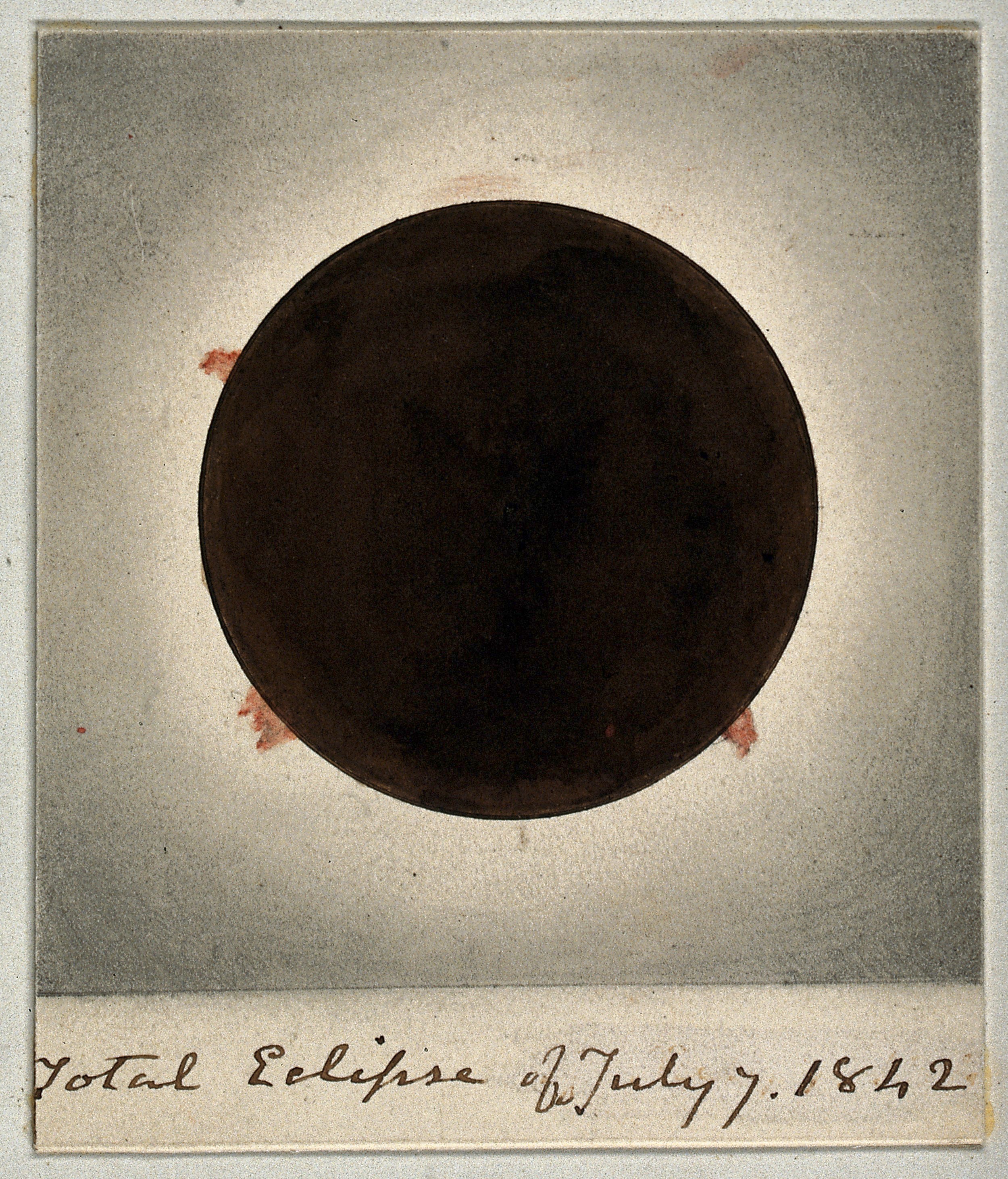

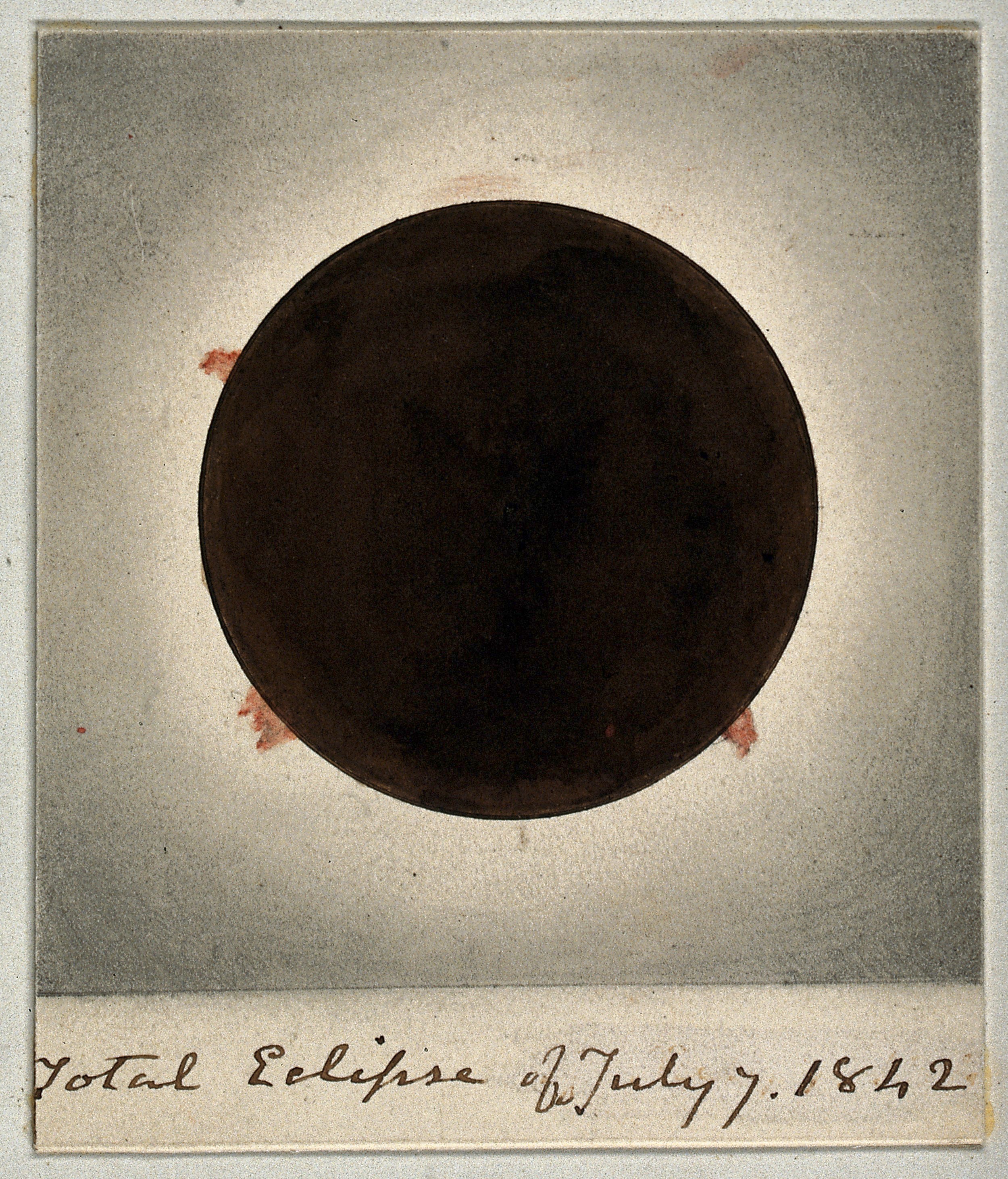

1842

Austrian astronomer Gian Alessandro Majocchi (1795–1854) captures the first photograph of a solar eclipse phase on a daguerreotype on July 8, 1842, using a 2-minute exposure.

1845

1845

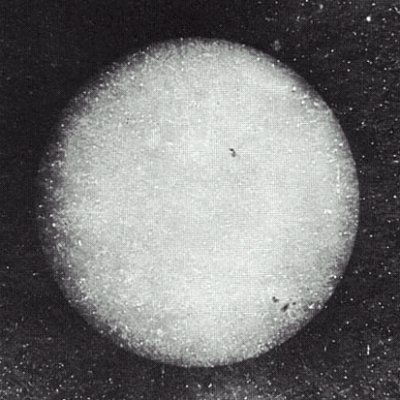

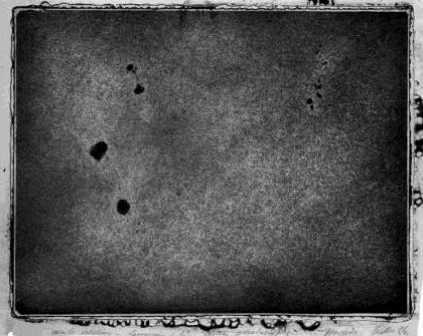

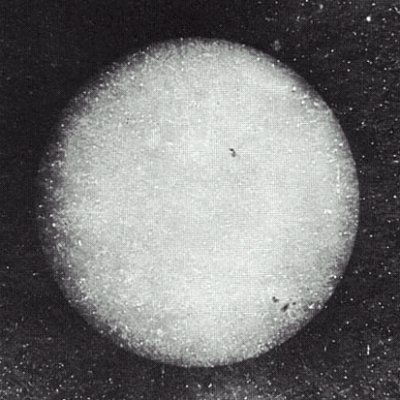

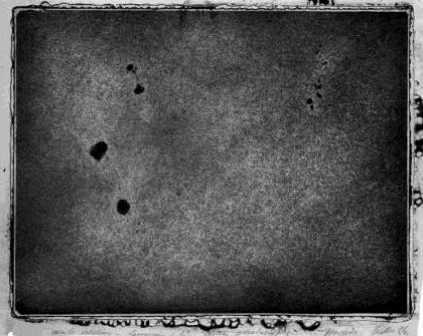

According to François Arago, a large number of solar daguerreotypes were obtained by Armand Hippolyte Louis Fizeau (1819–1896) and Jean Bernard Léon Foucault (1819–1868) at the Paris Observatory. One of these images, taken on April 2, 1845, has survived to this day.

Most likely, it is this photograph:

In 1970, the International Astronomical Union named a crater on the far side of the Moon after Fizeau.

In 1935, the IAU named a crater on the near side of the Moon after Foucault.

1849

William Cranch Bond (1789–1859) and John Adams Whipple (1822–1891) obtain a series of lunar daguerreotypes using a 15-inch (38 cm) refractor and 40-second exposures. They produced these images between 1849 and 1852.

A lunar crater was later named in honor of William Cranch Bond.

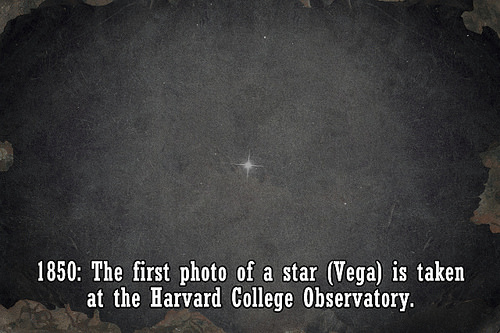

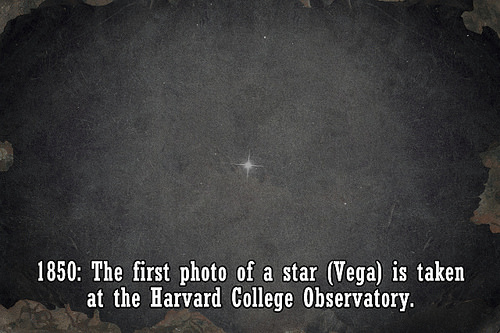

1850

The first photograph of a star, Vega (Alpha Lyrae), is captured by John Adams Whipple and George Phillips Bond. They used the 38 cm Harvard refractor with a 100 second exposure on July 17, 1850.

1851

1851

In Rome, Angelo Secchi (1818–1878) makes daguerreotypes of partial phases of a solar eclipse using a 6.5 inch (16.2 cm) refractor with an 8 foot (2.5 m) focal length. Better results follow six years later (see below).

1851

On March 22, 1851, George Phillips Bond writes in his notebook: “We managed to photograph Jupiter. Whipple took six plates and could make out the two main equatorial belts. The exposure time was about the same as for the Moon or just a bit longer.”

Amazingly, this predates the planetary images of the Henry brothers (1885–86) by more than 30 years.

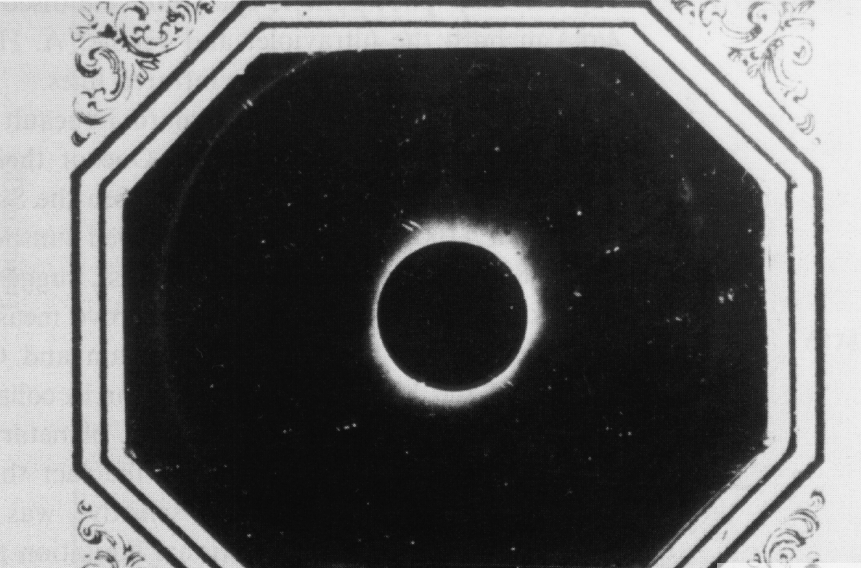

1851

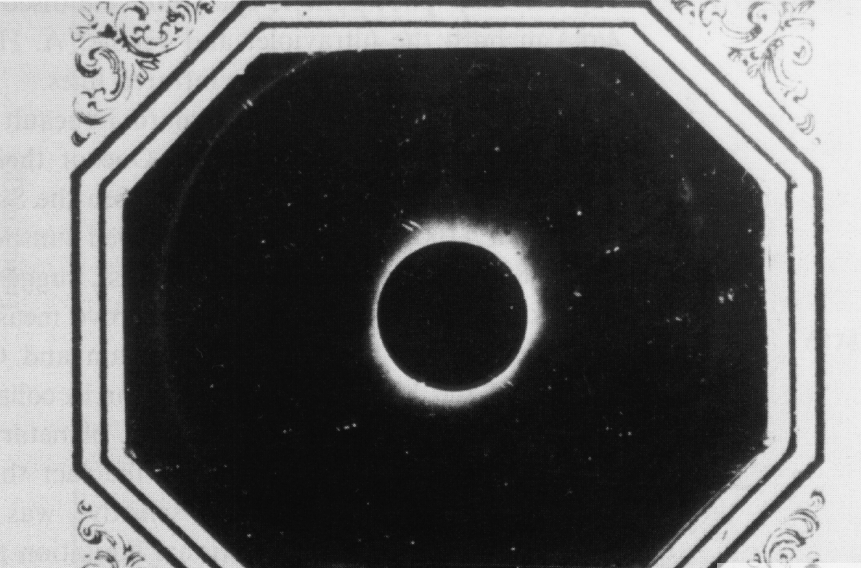

The first daguerreotype of a total solar eclipse is made by Berkowski in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad). He captured the corona and several prominences on July 28, 1851.

1857

1857

George Phillips Bond (1825–1865), son of William Cranch Bond, and John Adams Whipple photograph the double star Mizar (Zeta Ursae Majoris) and Alcor (80 Ursae Majoris) using the 15 inch (38 cm) Harvard refractor.

1857

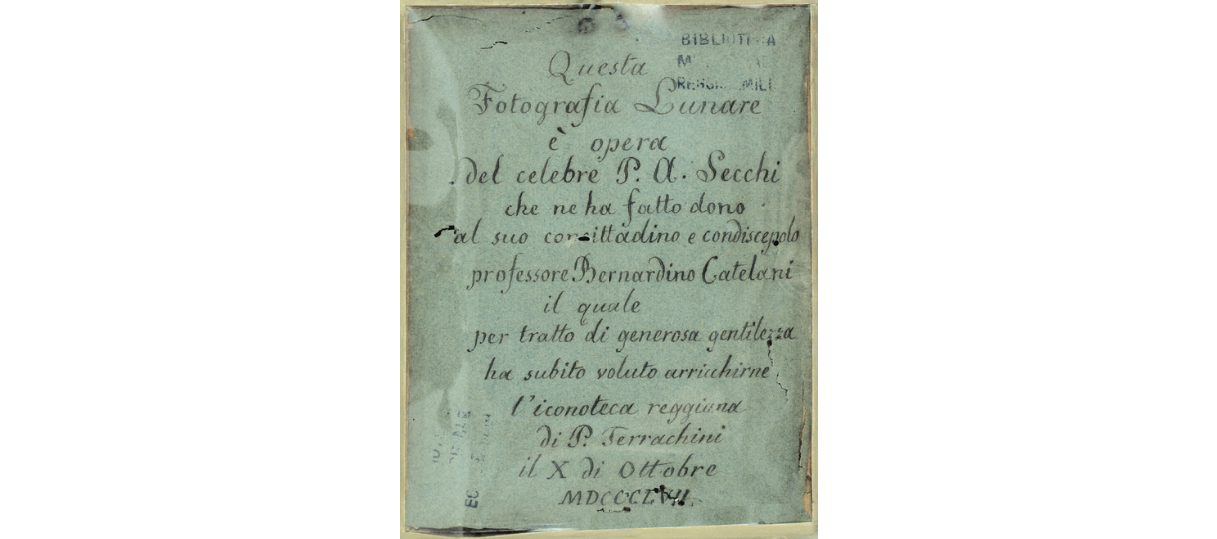

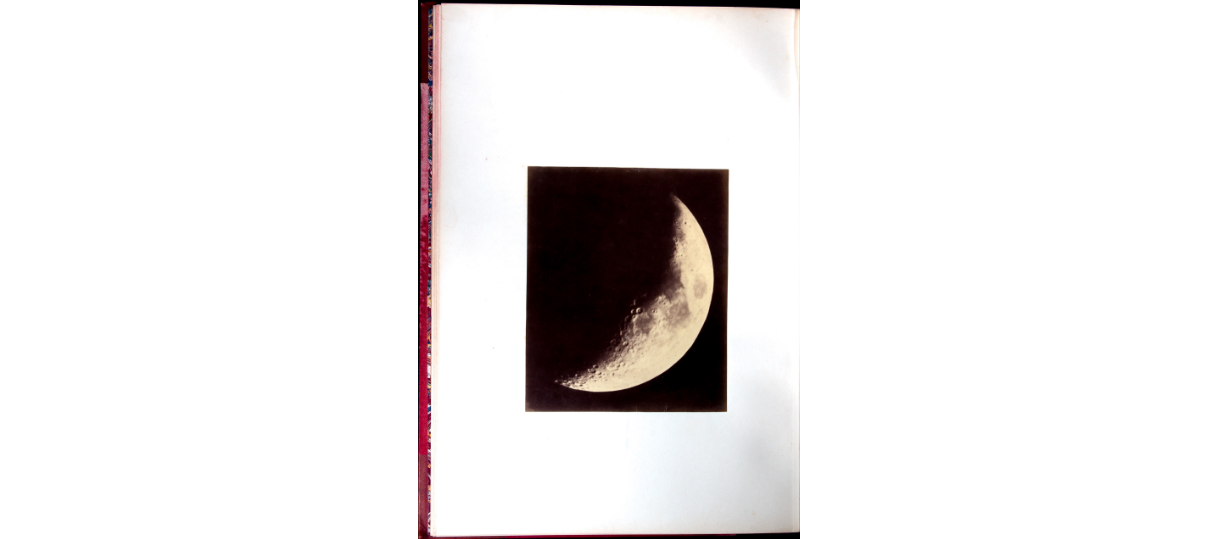

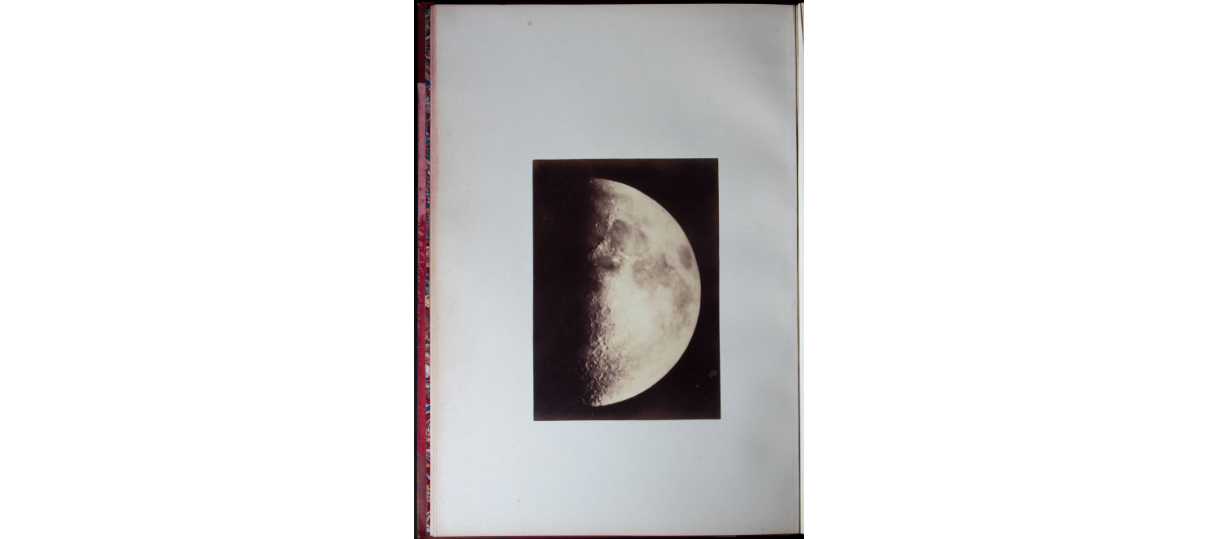

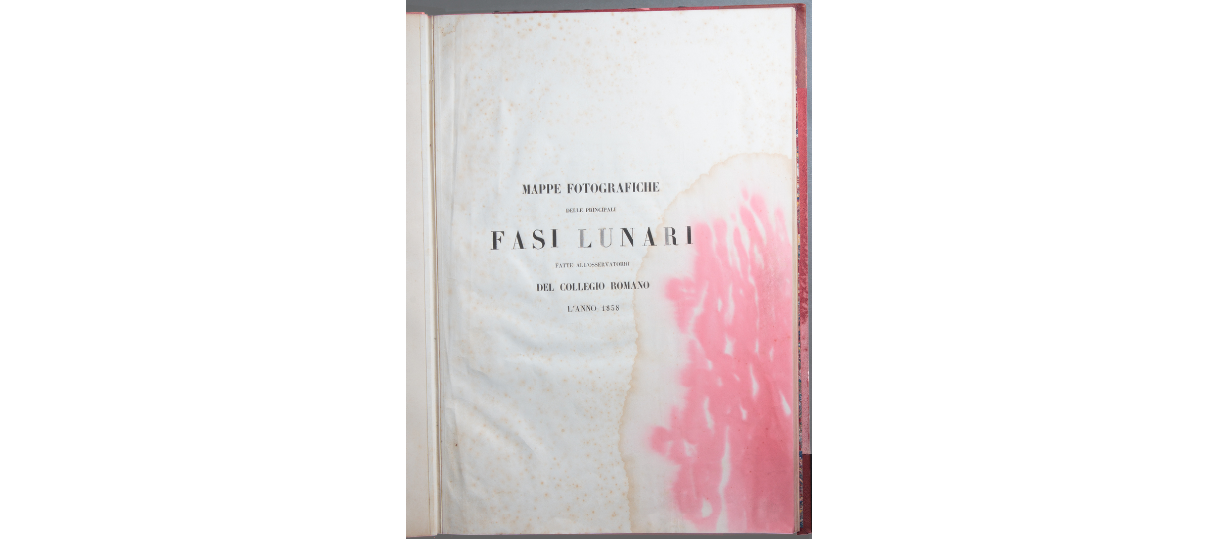

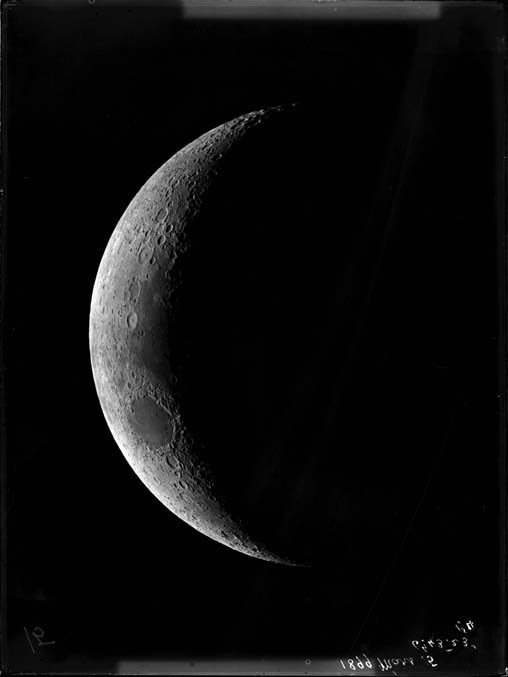

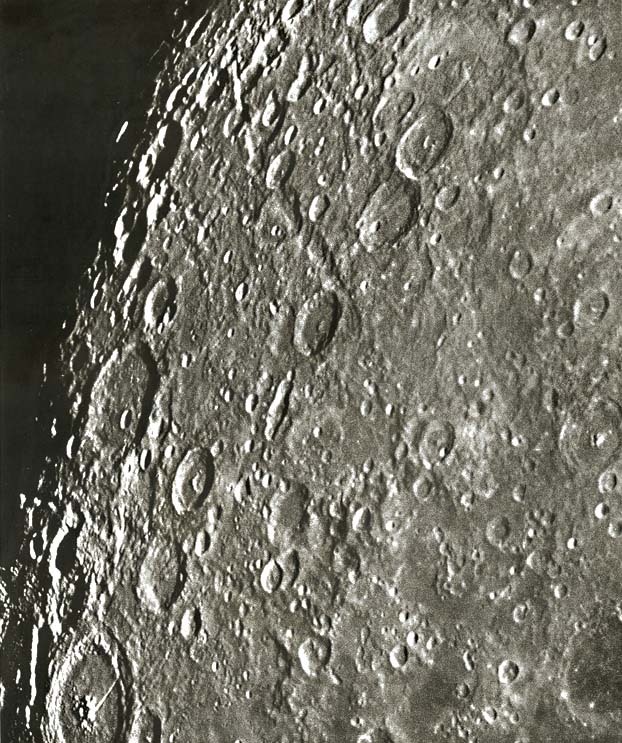

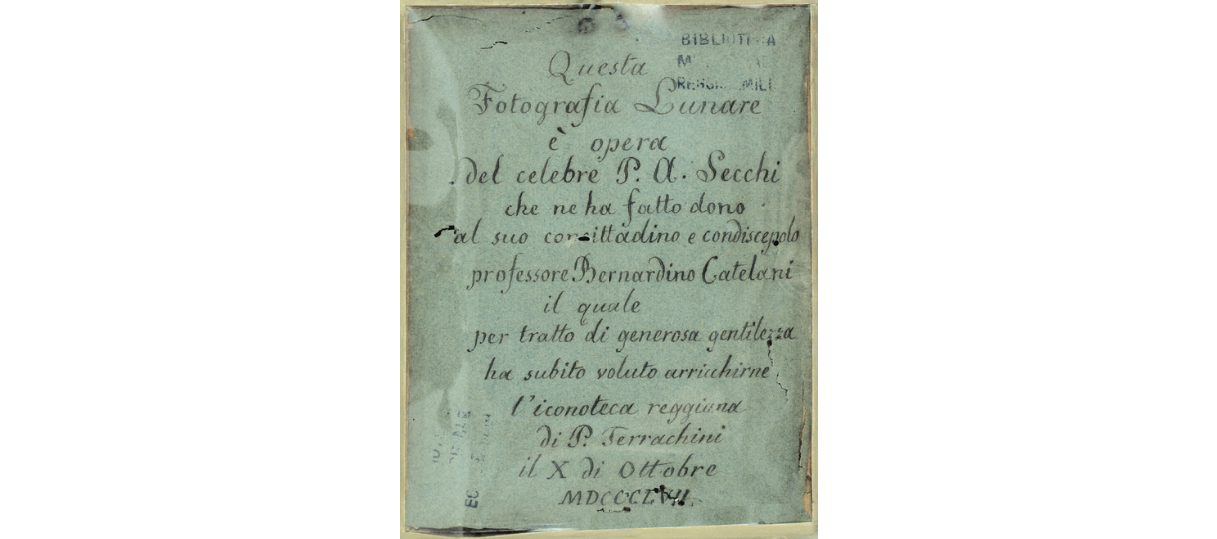

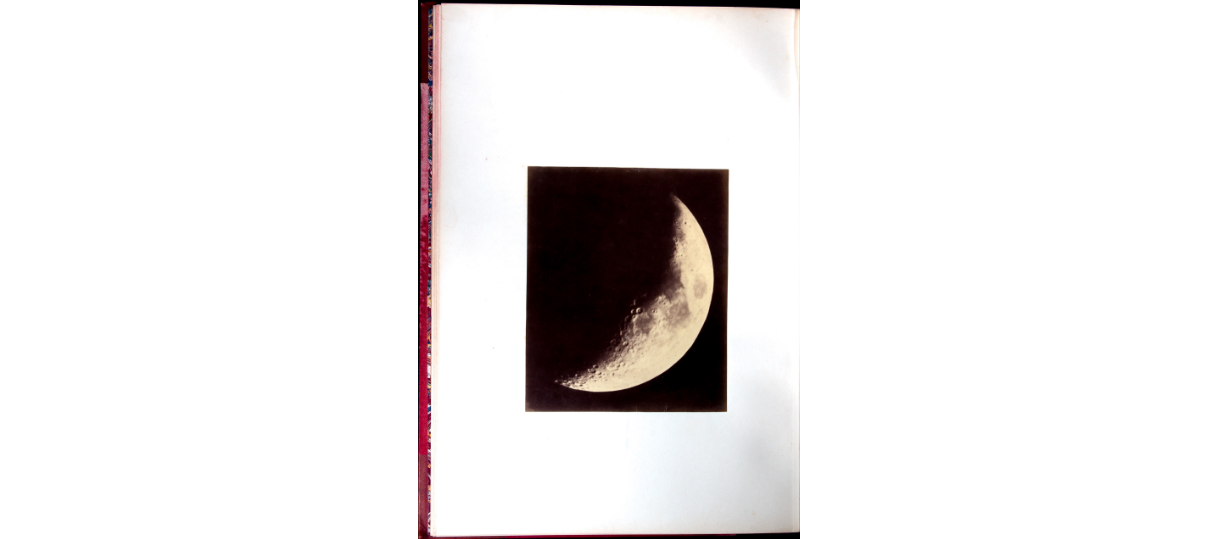

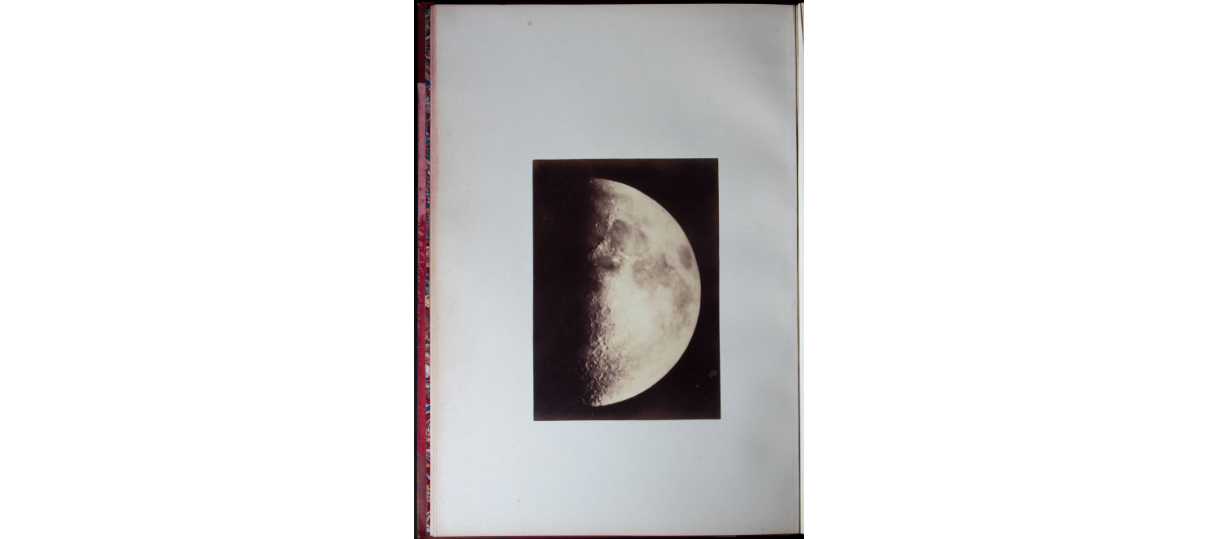

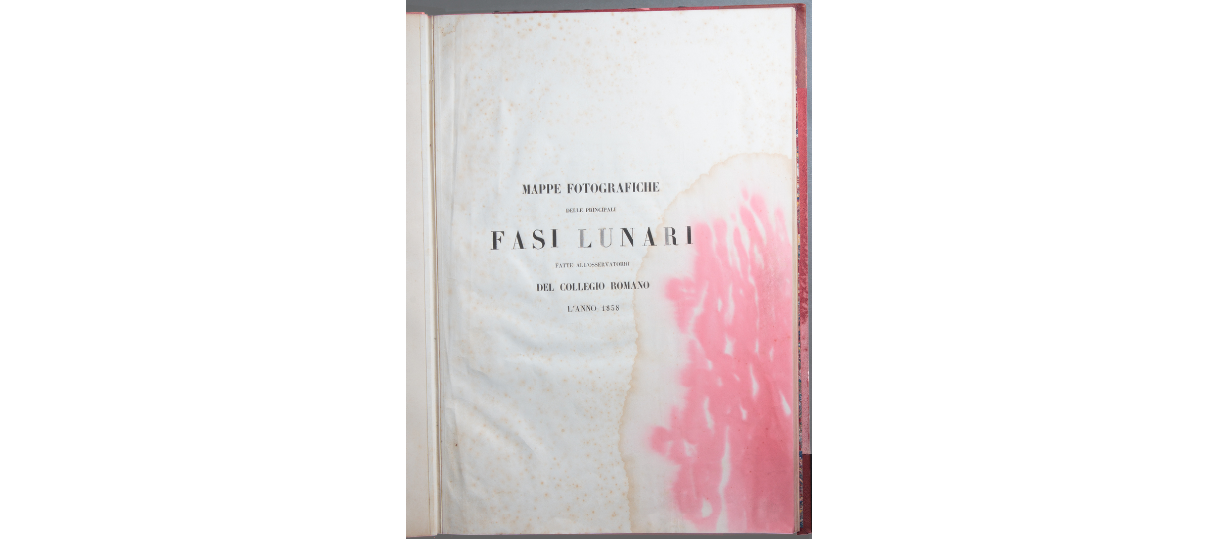

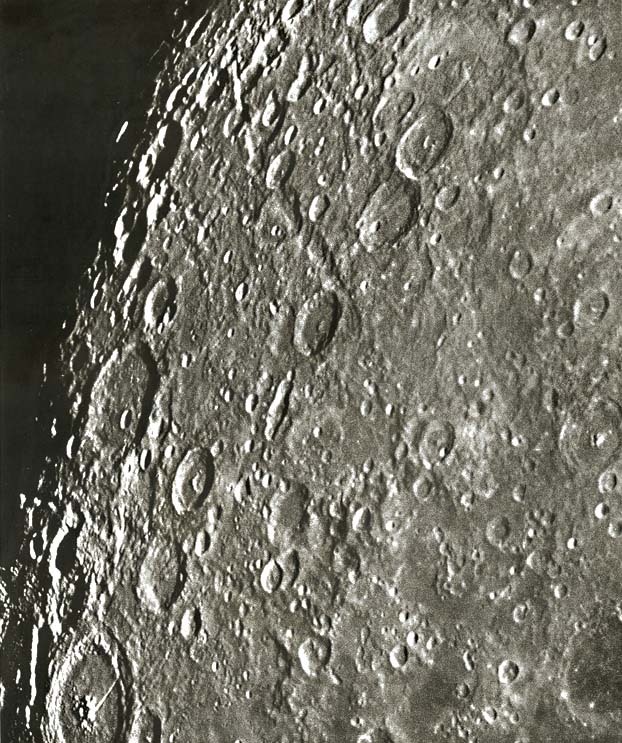

The Moon photographs shown here were found among the manuscripts of Naborre Campanini in the Panizzi Library. They are framed with handwritten notes and dates on the back (see fig. 1).

These preserved images document a series taken by Angelo Secchi together with Roman pharmacist Francesco Barelli in 1857.

These images were later included in Angelo Secchi’s Atlas of Lunar Phases.

1857

1857

Warren De la Rue obtains images of Jupiter and Saturn using a 13 inch (33 cm) reflector. The exposures (12 seconds for Jupiter and 60 seconds for Saturn) were unsuccessful.

1858

George Phillips Bond demonstrates that stellar magnitudes can be measured from astronomical photographs. This becomes the foundation of stellar photometry.

1858

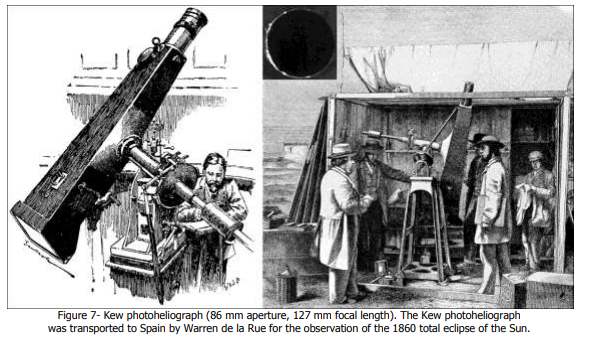

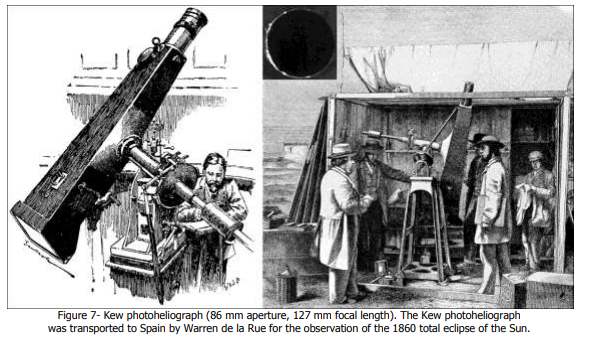

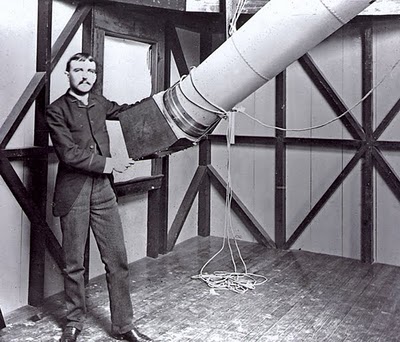

Daily solar photographs begin at Kew Observatory using Warren De la Rue’s photoheliograph. On clear days this produced a continuous record and a total of 2778 solar photographs were made between 1862 and 1872.

1858

Warren De la Rue attempts to photograph Donati’s Comet but without success.

1858

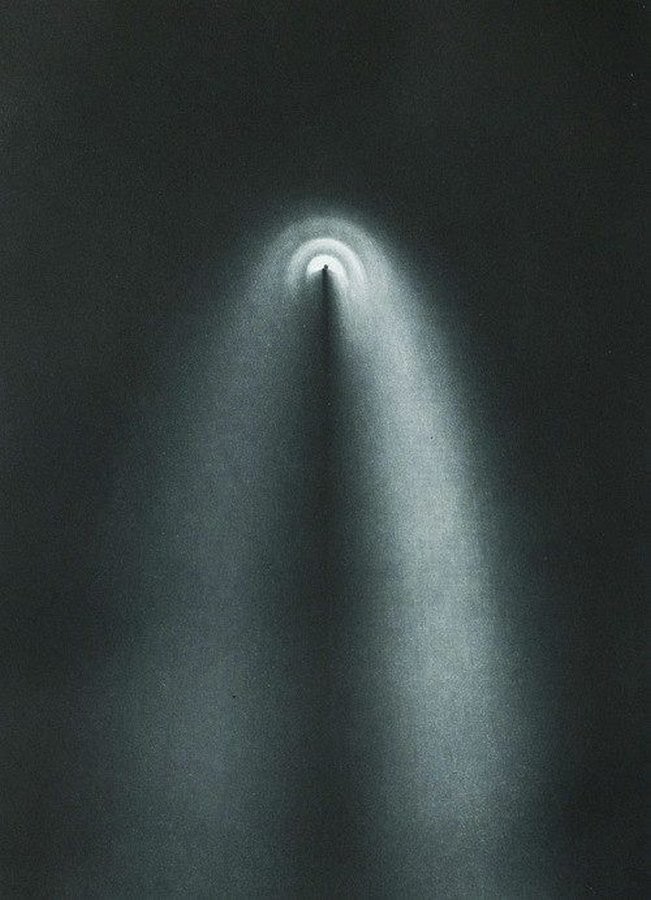

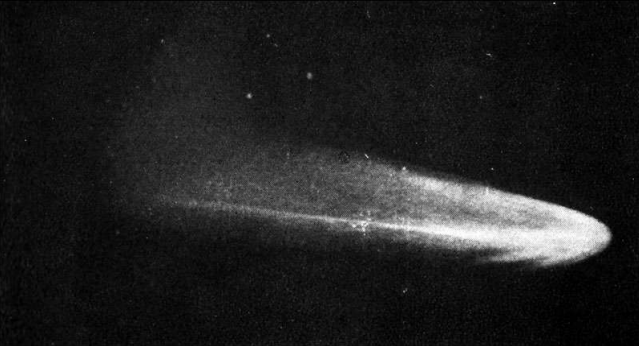

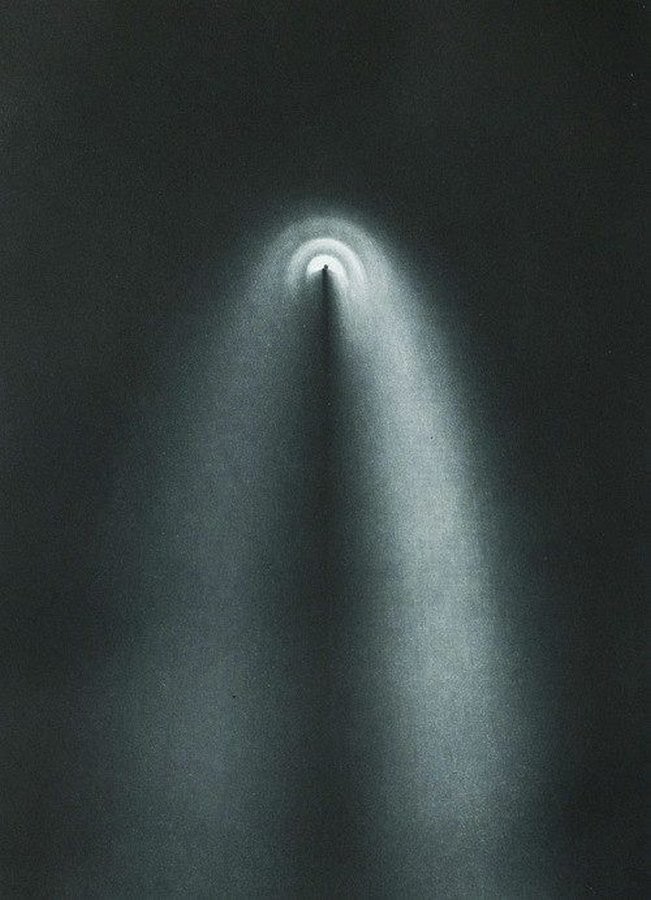

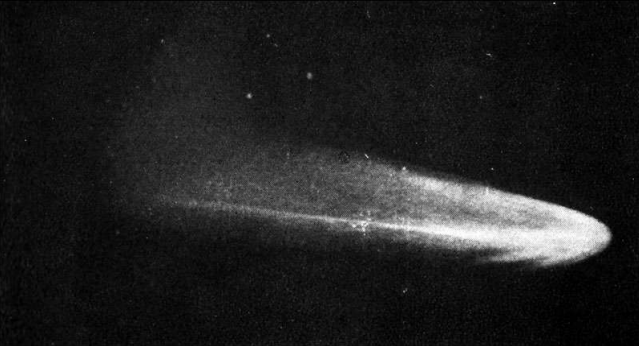

William Usherwood successfully captures Donati’s Comet with a 7 second exposure on Walton Common on September 27, 1858. At the time he was a miniature painter from Walton-on-the-Hill, Surrey.

For reference: Donati’s Comet (C/1858 L1, 1858 VI) is a long period comet discovered by Italian astronomer Giovanni Donati on June 2, 1858. After the Great Comet of 1811, it was considered the most beautiful comet of the 19th century. The previous major comet had appeared in 1854. Donati’s Comet was also the first comet ever photographed. It reached perihelion on September 30, when its tail stretched 40 degrees long and 10 degrees wide. It made its closest approach to Earth on October 10, 1858. Its next return is expected in the 39th century, around the year 3811.

After digging through half the internet, it seems many sources attribute this photograph to William Usherwood. I can’t guarantee it’s accurate, but here it is for the timeline:

1860

1860

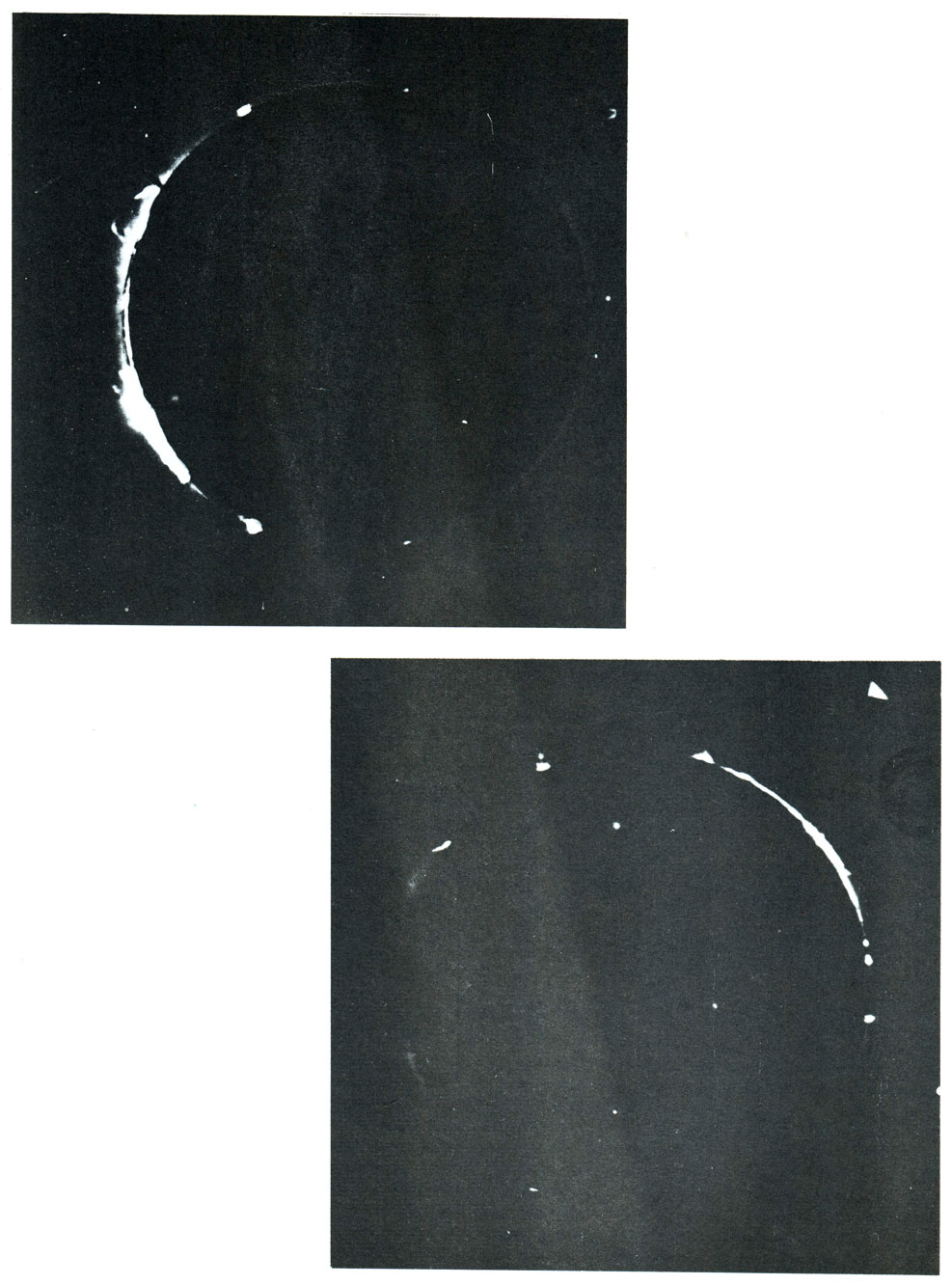

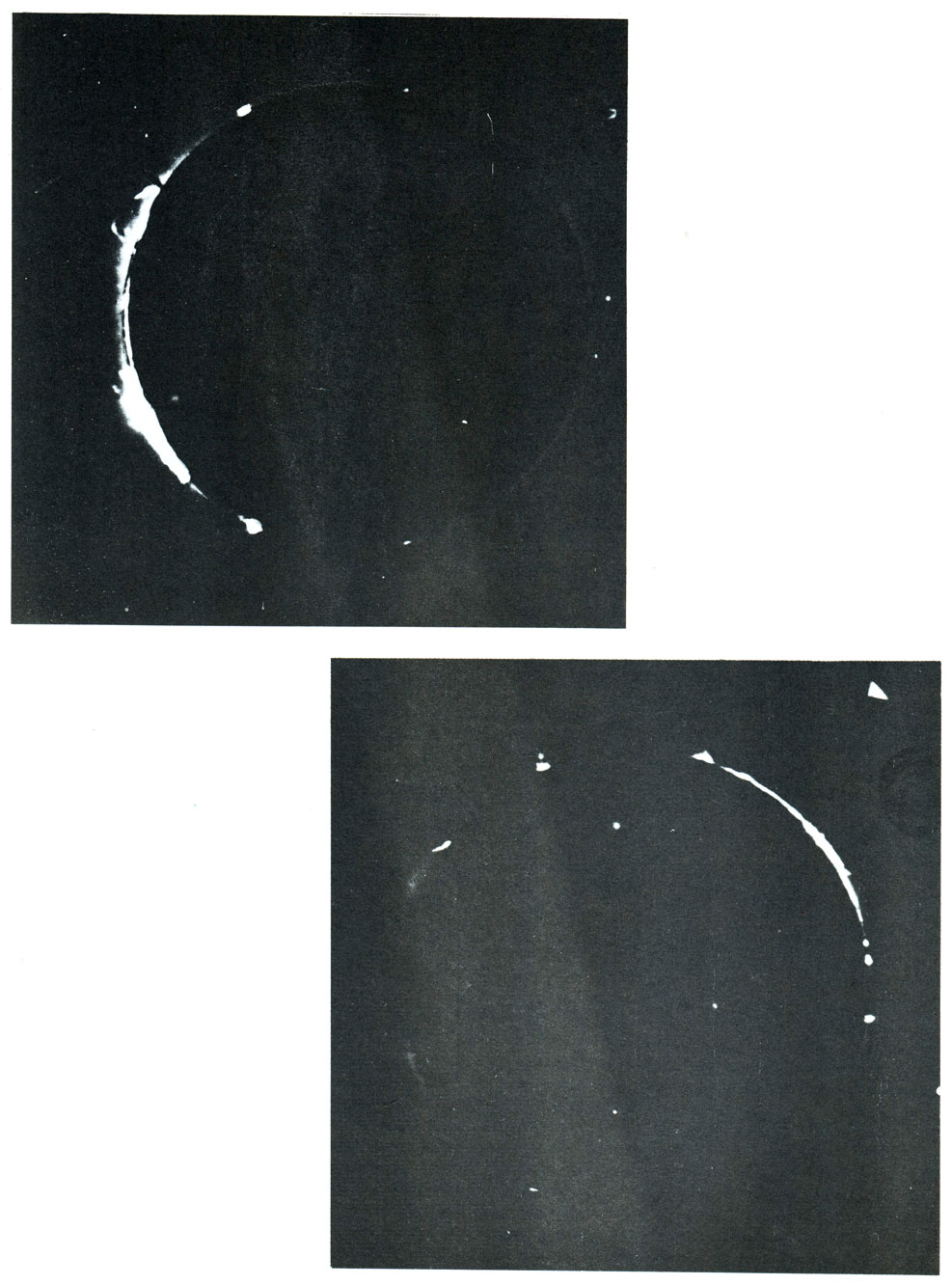

Warren De la Rue photographs the total solar eclipse at Rivabellosa, Spain, on July 18, using the Kew photoheliograph and 60 second exposures.

If you ever feel too lazy to pack your astro gear and drive out of the city, remember how hard it was for De la Rue. He traveled to Spain with a single goal: to study the glowing features at the edge of the lunar disk during totality and determine whether they were true solar prominences or just atmospheric effects.

The expedition had to haul a massive photoheliograph along with a cast iron mount. On eclipse day they faced plenty of problems: clouds that fortunately cleared just in time, a fire started by a careless boy who was smoking glass for villagers, and a crowd of two hundred curious onlookers who finally had to be pushed back by a detachment of guards.

In the end, De la Rue managed to obtain 35 good photographs, including two taken at the moment of totality. Two years later, John Lee described them as “large and exceptionally clear images” when presenting De la Rue with the Royal Astronomical Society’s gold medal.

The images shown here capture the very beginning (top) and the very end (bottom) of totality. According to De la Rue, they reproduce the glowing prominences with a clarity and precision that would be impossible with visual observation alone.

1861

James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879) demonstrates a system for creating color photographs using three black and white exposures taken through red, green and blue filters. Modern astrophotographers still use this exact concept with dedicated astro cameras and LRGB filter wheels.

1861

Warren De la Rue mentions the possibility of conducting a photographic survey to create a complete star map of the sky.

1864

Henry Draper (1837–1882) photographs the Moon using a 15.5 inch (40 cm) reflector he built between 1864 and 1865.

By the way, yes, Henry was the son of John William Draper, the man who made the first photograph of the Moon.

This small lunar crater (above and to the left) is named after him:

The crater below and to the right has the same name with the “C” designation.

1864

William Huggins records the spectrum of NGC 6543 (the Cat’s Eye Nebula), a bright planetary nebula in Draco. Instead of a series of spectral lines he finds only one bright emission line. He concludes that this must come from a gas, proving for the first time that some “nebulae” are actually gaseous objects and not clusters of unresolved stars.

1865

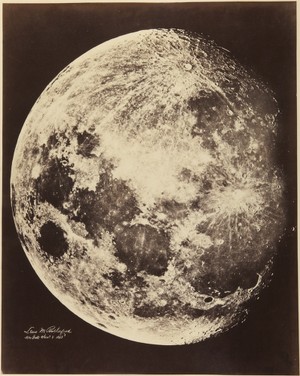

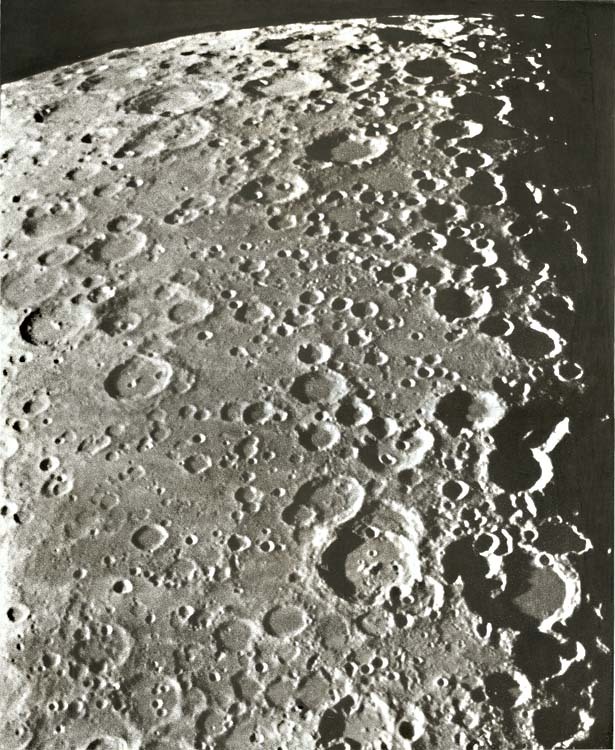

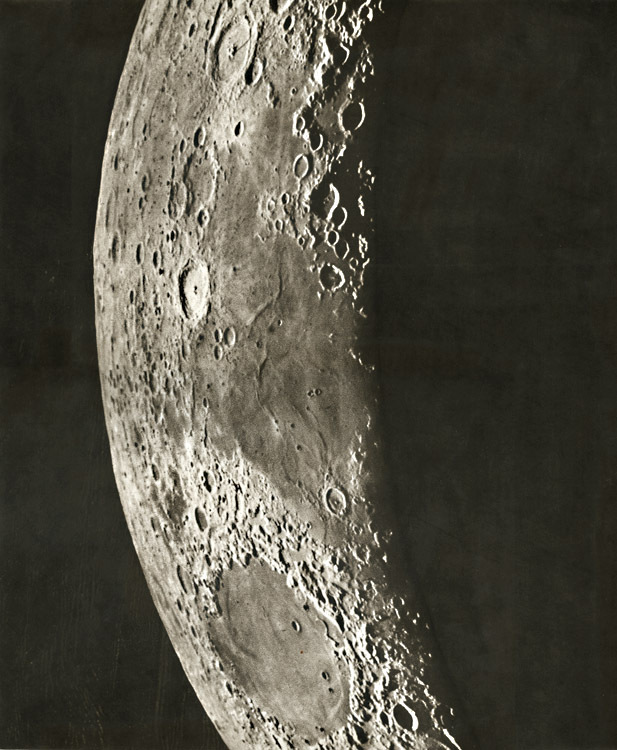

Lewis Morris Rutherfurd captures excellent photographs of the Moon using a specially corrected 11.25 inch (29 cm) photographic lens. This was the first true photographic telescope in the world, also known as an astrograph.

I think it’s beautiful.

1871

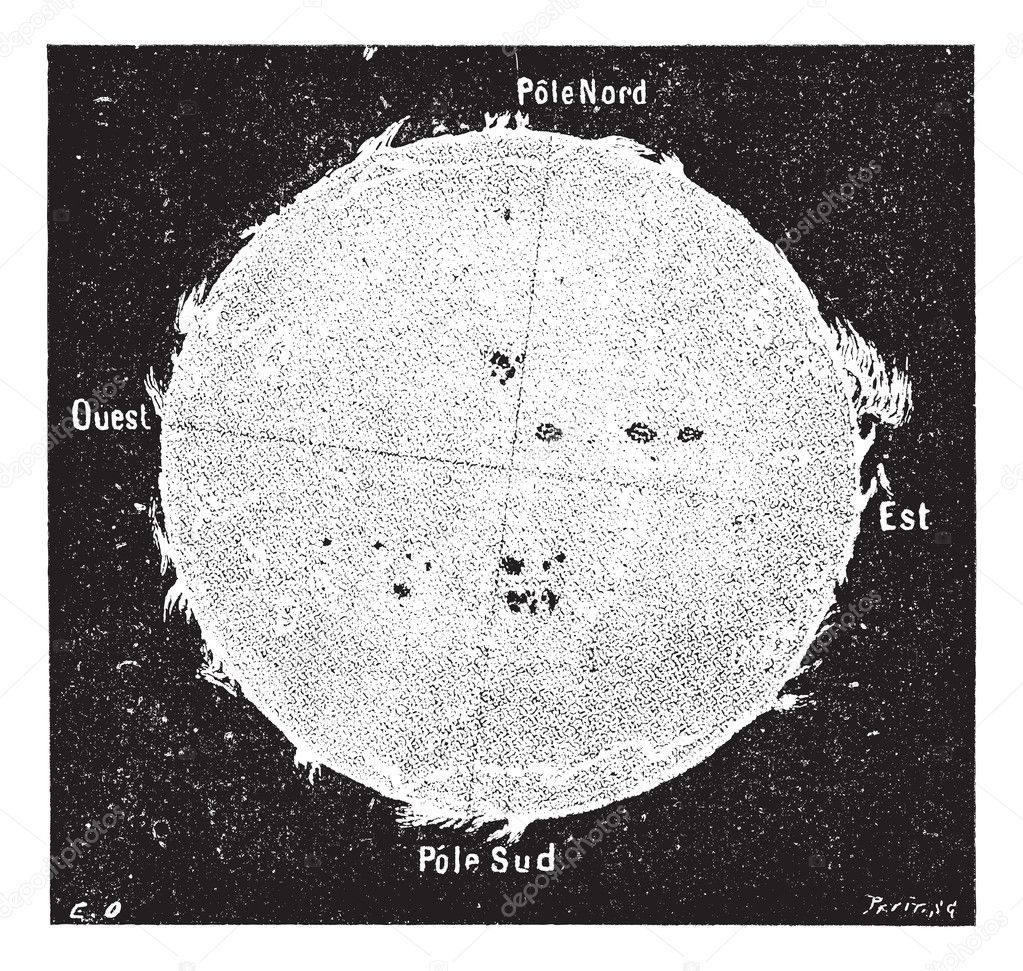

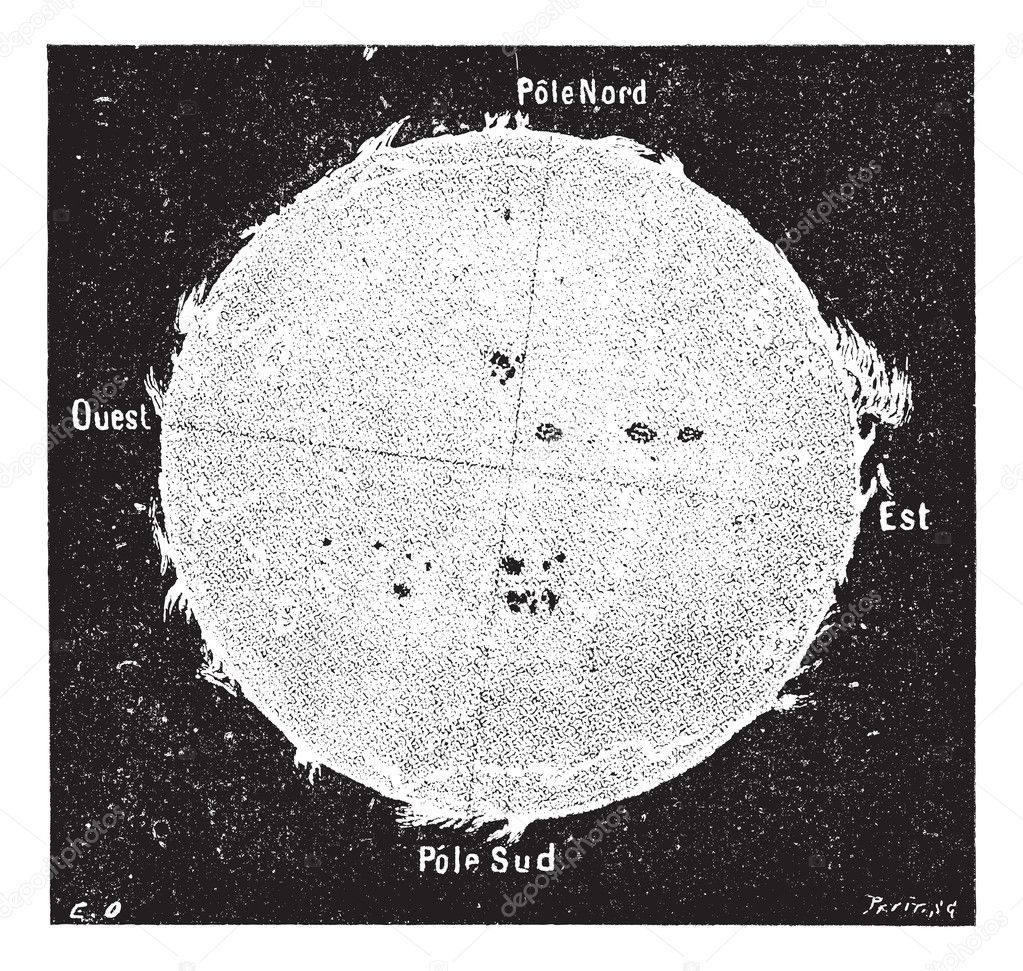

German astronomer Hermann Carl Vogel (1841–1907) obtains excellent photographs of the Sun using an 11.5 inch (29.4 cm) refractor at Bothkamp, Germany. The telescope was equipped with an electric shutter, allowing exposures as short as 1/5000 to 1/8000 of a second.

This illustration, dated to the same year, may have been based on his photographs:

Maybe someone will recognize the signature and identify the illustrator.

Vogel, along with Scheiner, discovered the periodic velocity changes of Algol, as well as the spectroscopic binarity of Alpha Virginis (Spica) and Beta Lyrae. Together with G. Müller, he conducted visual spectroscopic observations of 4051 stars. In 1882 he published “Spectroscopic Observations of Stars,” the first spectroscopic catalog of stars down to magnitude 7.5, covering the region from 20° north to 1° south declination.

He also carried out spectroscopic studies of Solar System planets from Mercury to Neptune, comets, nebulae, and novae. In the laboratory he analyzed meteorites with spectral methods in search of carbon compounds. He also studied the spectrum of auroras.

A lunar crater, a Martian crater, and asteroid 11762 were named in his honor.

1872

Henry Draper photographs the spectrum of a star for the first time in history. The target was Alpha Lyrae (Vega) and he used a 28 inch (72 cm) reflector equipped with a quartz prism.

1873

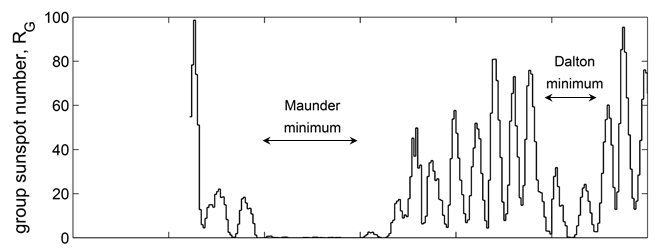

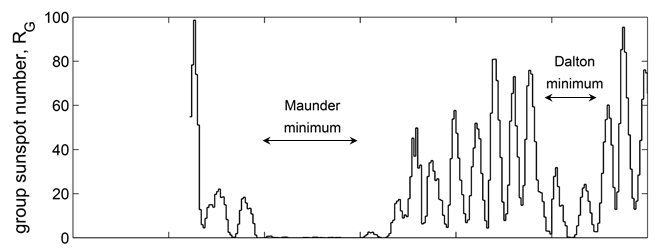

Edward Walter Maunder (1851–1928) installs a photoheliograph at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich for daily solar imaging. Maunder is best known for his studies of sunspots and the solar magnetic minimum that occurred between 1645 and 1715, now known as the Maunder Minimum.

Here is a graph showing the dramatic drop in sunspot numbers during that period:

1874

1874

On December 8, 1874, Pierre Jules César Janssen (1824–1907) develops the “Revolving Photography” method to record the transit of Venus across the Sun. This remarkable device functioned as an early high speed camera, capable of capturing 100 images per hour.

1875

1875

Henry Draper photographs the spectra of bright stars using an 11 inch (28 cm) refractor and a quartz prism placed next to the photographic plate.

1876

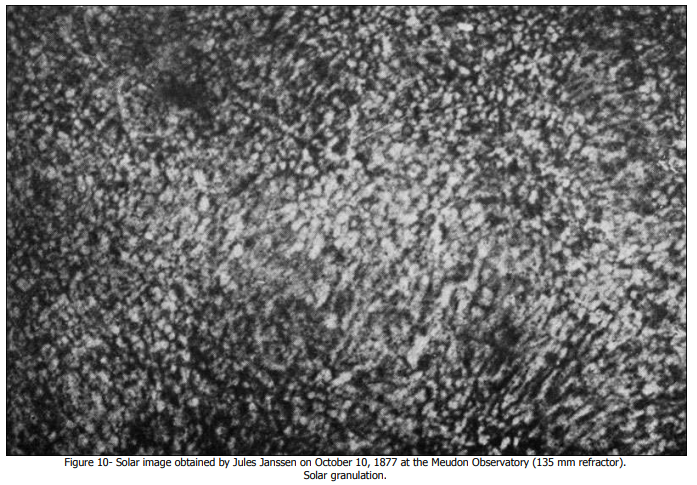

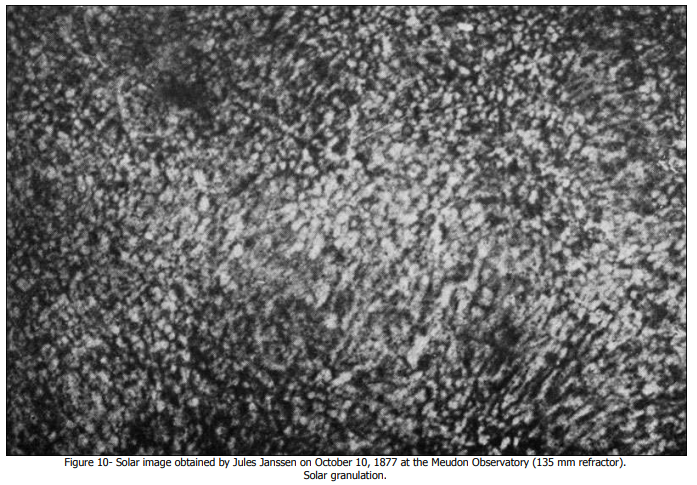

In 1876, Jules Janssen presents his first solar photographs to the French Academy of Sciences. These images, showing the Sun with diameters from 10 to 70 cm, were taken with a 140 mm refractor using exposures from 1/500 to 1/6000 second. In 1877 and 1878, Janssen obtains the first large collection of solar photographs showing solar granulation, the visible structure of the Sun’s photosphere.

1879

1879

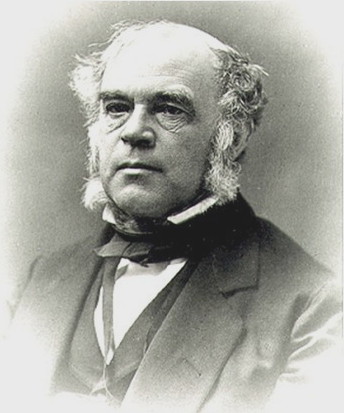

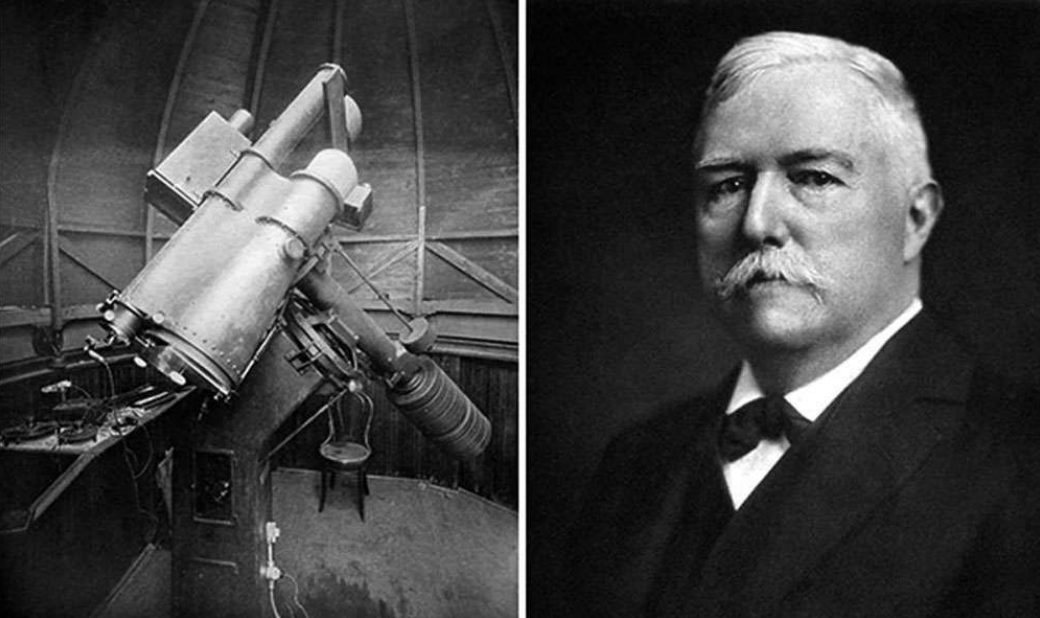

Andrew Ainslie Common (1841–1903) photographs Jupiter using a 36 inch (91 cm) reflector with a focal length of 17.4 feet (5.30 m) and a 1 second exposure.

1880

1880

Henry Draper captures the first photograph of the Orion Nebula (M42) on September 30, 1880, using an 11 inch (28 cm) Alvan Clark refractor and a 51 minute exposure. He goes on to photograph M42 two more times: in March 1881 and on March 14, 1882, with even longer exposures of 104 and 137 minutes.

1881

1881

It was once believed that Janssen was the first to successfully photograph a comet when he imaged Tebbutt’s Comet (1881 III) on June 30, 1881. Janssen used a 50 cm lens and a 30 minute exposure. The same comet was photographed by Henry Draper, Andrew Ainslie Common and Margaret Huggins.

However, we now know that the true first comet photograph was made earlier by William Usherwood, who captured Donati’s Comet on September 27, 1858 (mentioned above).

1882

1882

David Gill (1843–1914) photographs the Great September Comet of 1882 using a portrait lens with a 63 mm aperture (f/4.5).

1882

1882

Henry Draper’s Orion Nebula photograph with an exposure of more than two hours:

1883

1883

Andrew Ainslie Common photographs the Orion Nebula (M42) using his 36 inch (91 cm) reflector on January 30, 1883. The 37 minute exposure reveals stars too faint to see with the eye, appearing for the first time only on the photographic plate.

On February 28, 1883, he obtains an even deeper image with a 60 minute exposure.

1885

1885

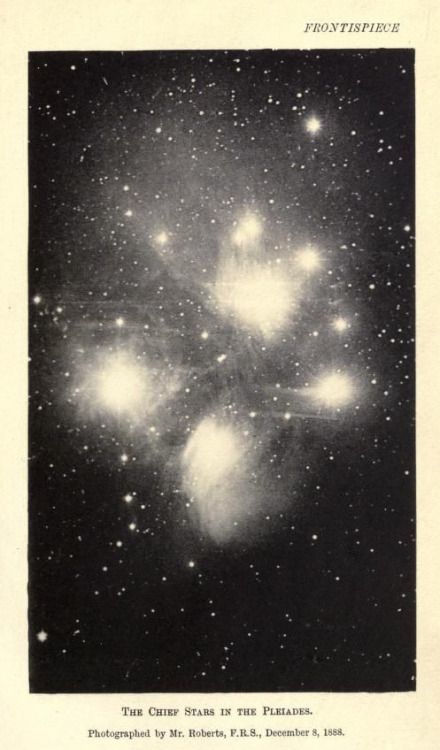

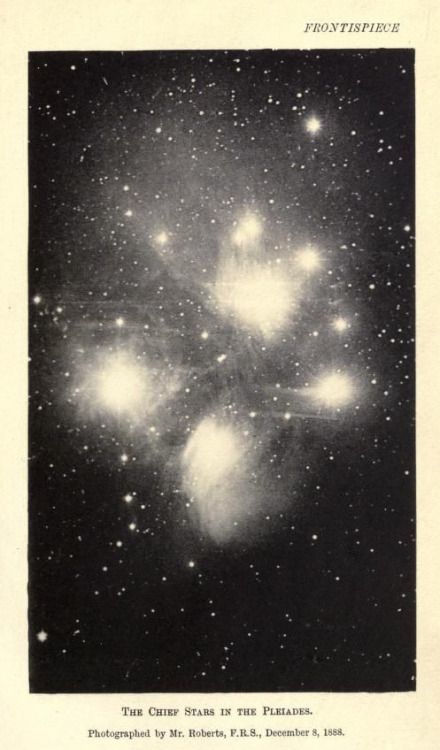

Between 1885 and 1899, Isaac Roberts (1829–1904) produces a remarkable series of astrophotographs and publishes two volumes of results (the first in 1893 and the second in 1899), both titled *Photographs of Stars, Star Clusters and Nebulae*.

Here is his photograph of the Pleiades, dated 1888:

1885

1885

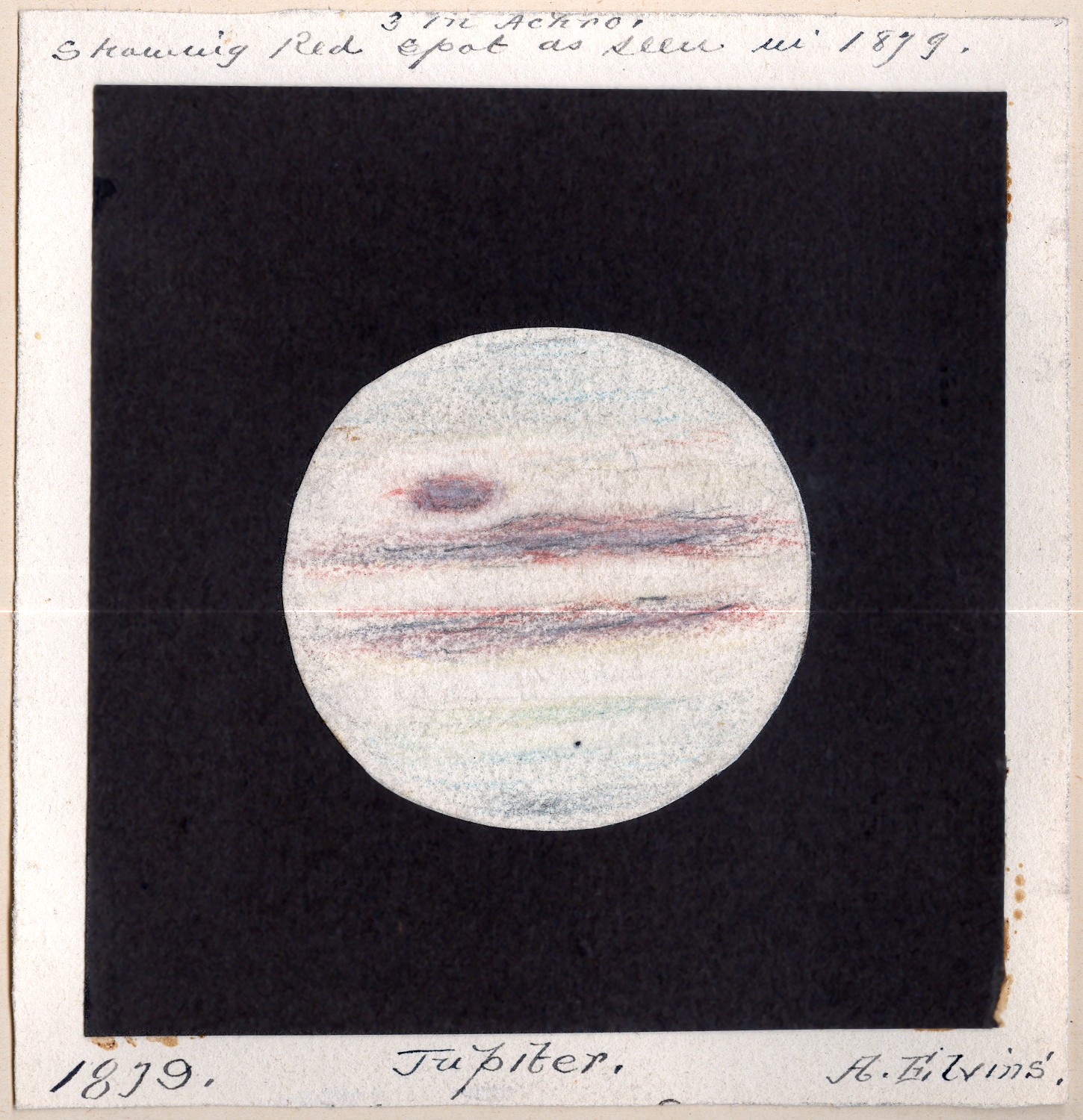

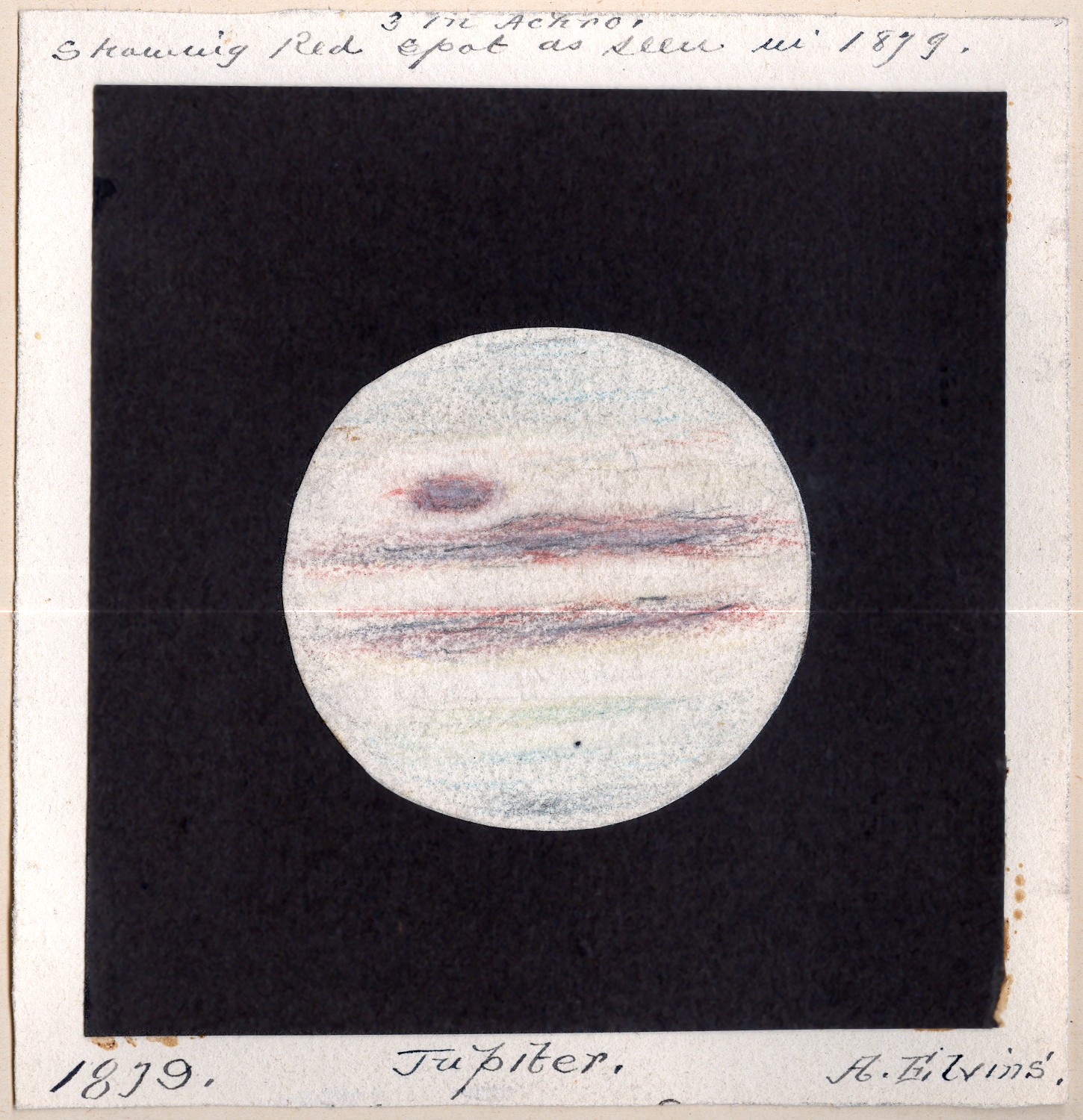

Between 1885 and 1886, the Henry brothers, Paul Henry (1848–1905) and Prosper Henry (1849–1903), photograph Jupiter and Saturn using the 33 cm refractor of the Paris Observatory (focal length 3.43 m).

1888

1888

William Henry Pickering (1858–1938) uses a 13 inch Boyden refractor from Harvard to capture some of the earliest photographs of Mars, taken from Cambridge, Massachusetts.

1890

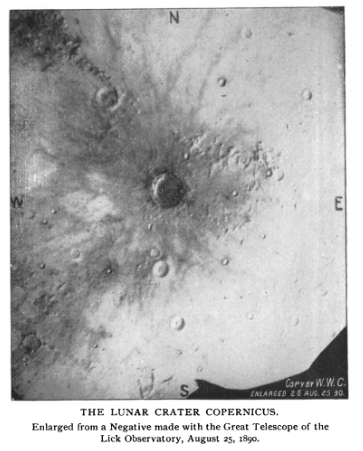

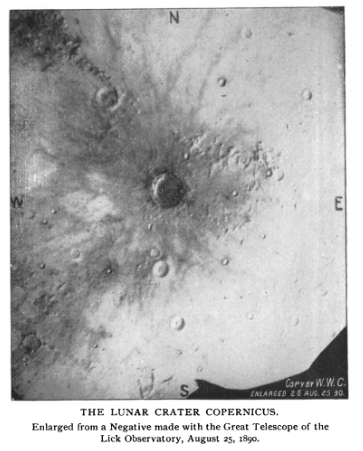

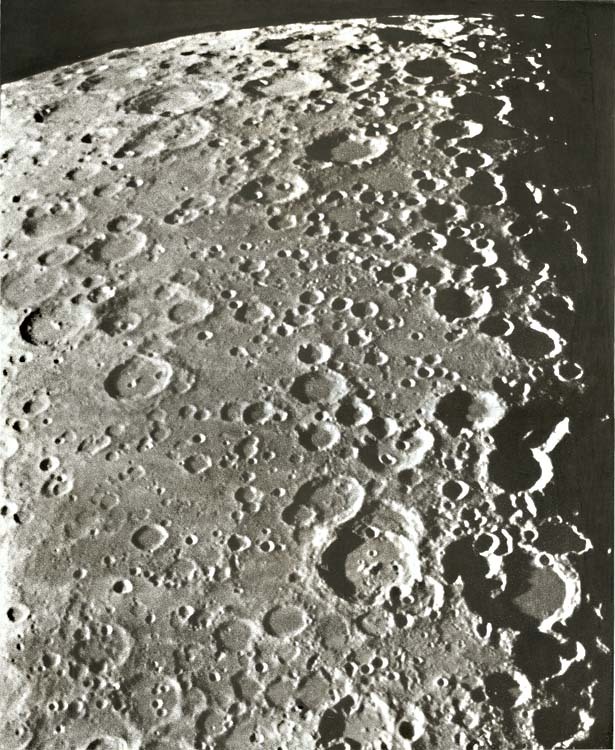

Edward Singleton Holden (1846–1914) produces high resolution photographs of the Moon.

1894

1894

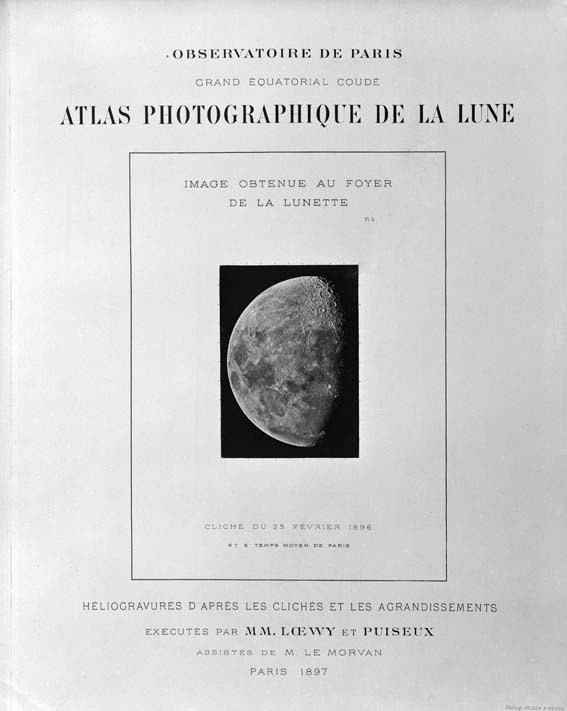

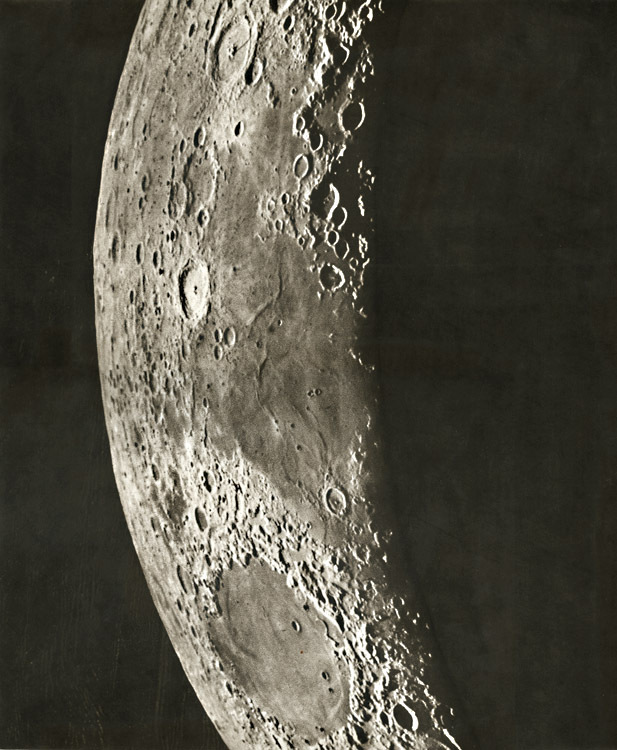

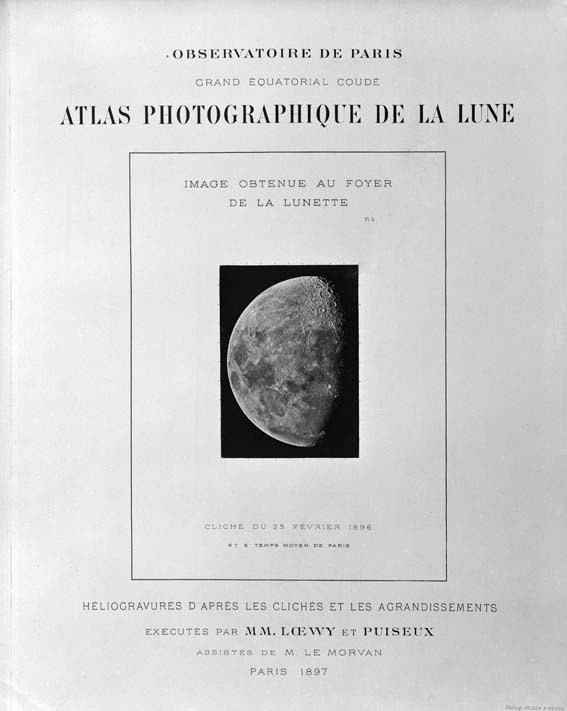

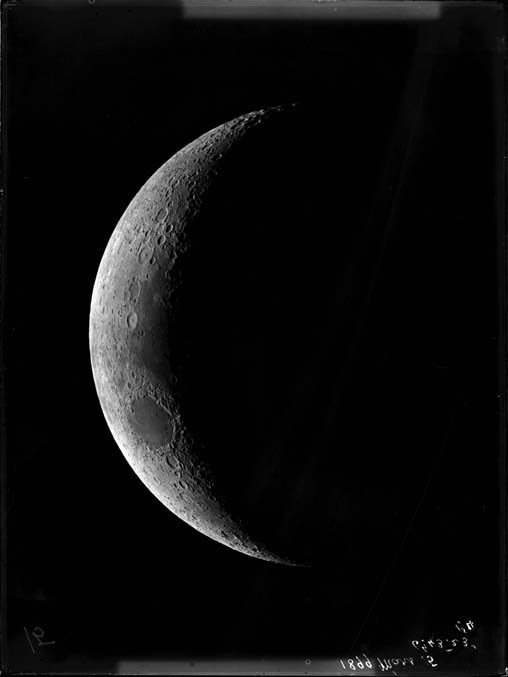

Between 1894 and 1910, Maurice Loewy (1833–1907) and Pierre Henri Puiseux (1855–1928) capture 6000 lunar photographs over 500 nights using the 60 cm Paris Observatory Coudé refractor. These images form the basis of the first complete lunar atlas, *L’Atlas Photographique de la Lune*.

1898

1898

William Edward Wilson uses his cinematic-style apparatus to record sunspots. It was capable of taking 100 photographs per hour.

1899

German astronomer Julius Scheiner (1858–1913) photographs the spectrum of the spiral galaxy M31 with an exposure of more than 7 hours, proving that the Andromeda Nebula is made of individual stars.

The only 1899 Andromeda image I managed to find, though, is this one by Isaac Roberts:

1901

1901

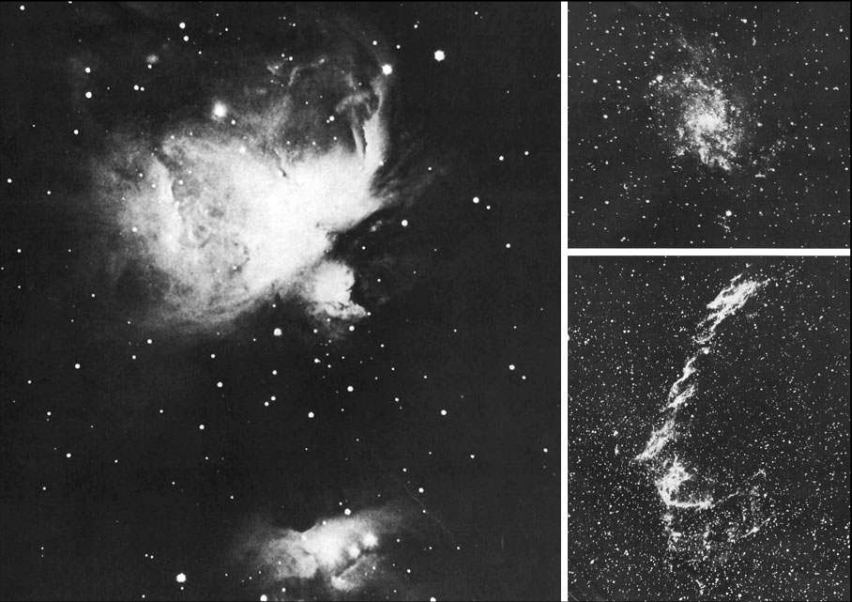

George Willis Ritchey (1864–1945) captures a series of excellent nebula photographs using the 60 cm Mount Wilson reflector between 1901 and 1902.

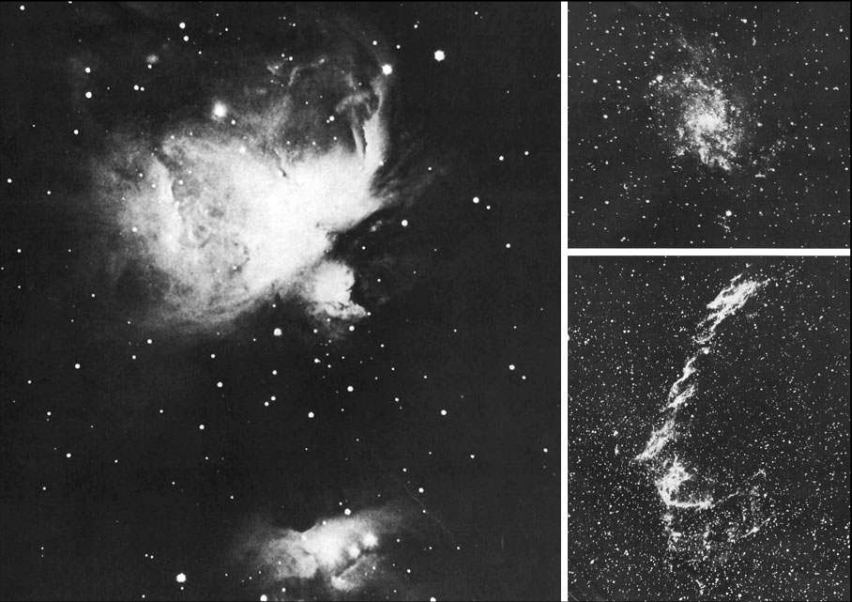

And here are images taken by William Wilson using a 60 cm Grubb reflector: M42 (1897), M33 (1899) and NGC 6992 (1899), each with 90 minutes of exposure.

1903

1903

Pierre Janssen publishes his monumental photographic solar atlas, *Atlas de Photographies Solaires*.

1909

George Willis Ritchey records several star clusters and nebulae with the Mount Wilson reflector using exposures of up to 11 hours spread over multiple nights.

For example, here is M3:

And here is his image of Bode’s Galaxy, taken a few years later:

1911

1911

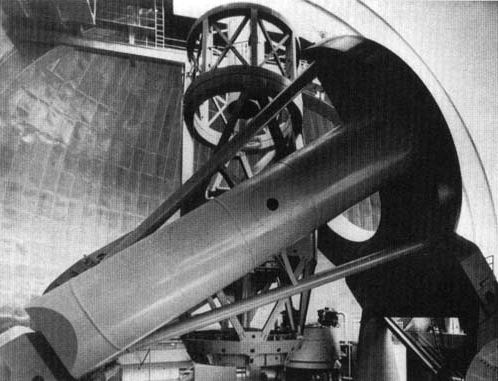

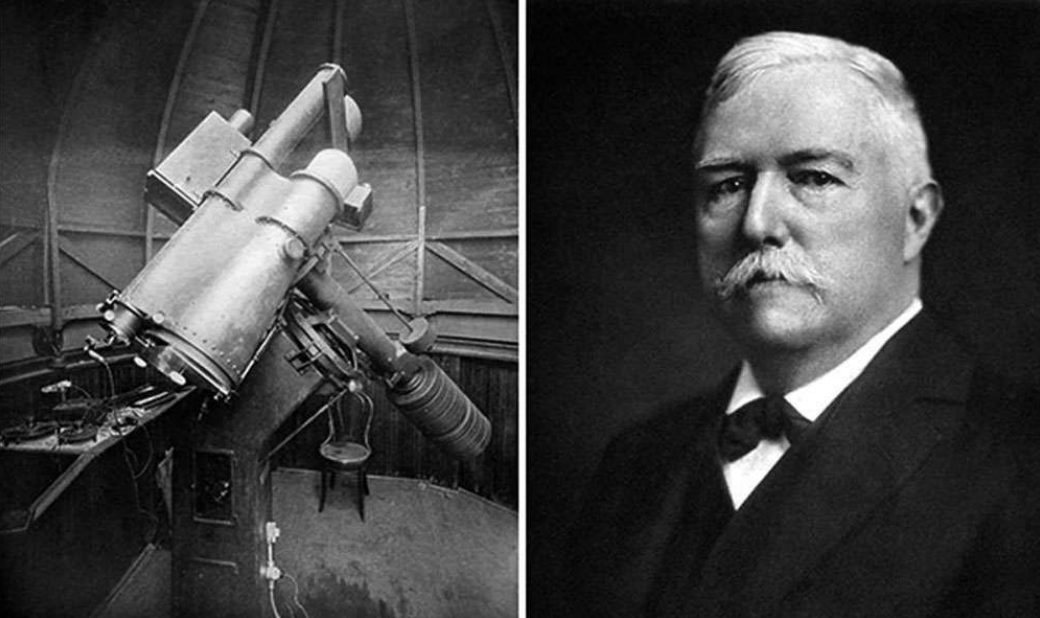

Edward Emerson Barnard captures excellent photographs of Saturn using the 1.52 meter Mount Wilson reflector.

1913

1913

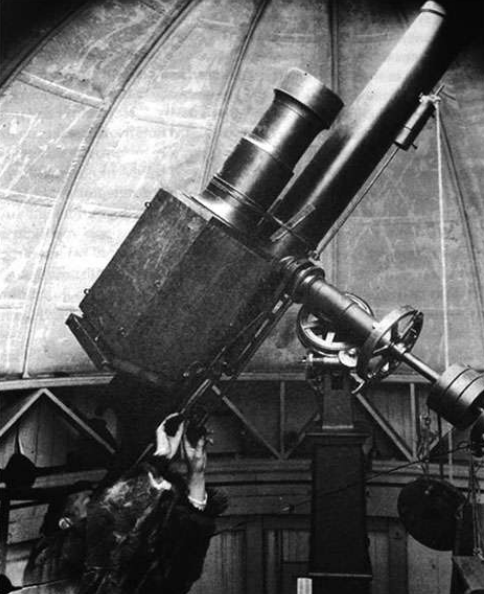

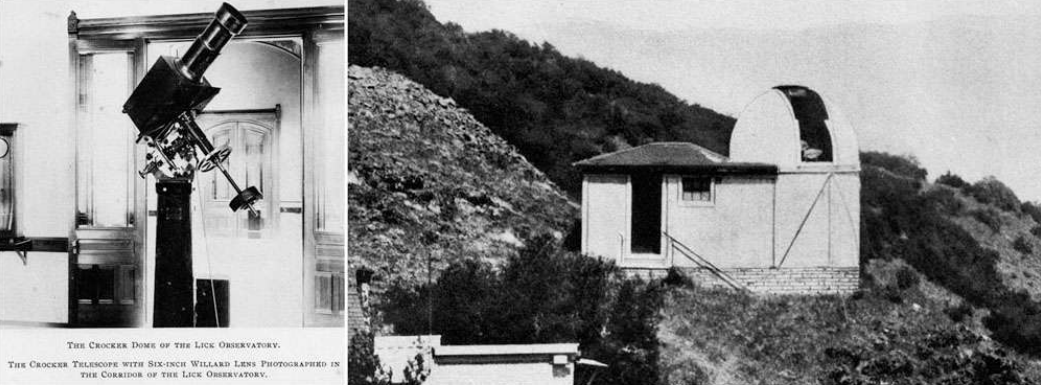

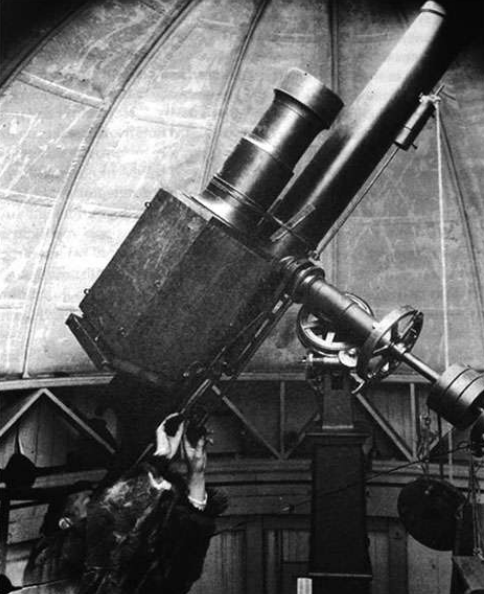

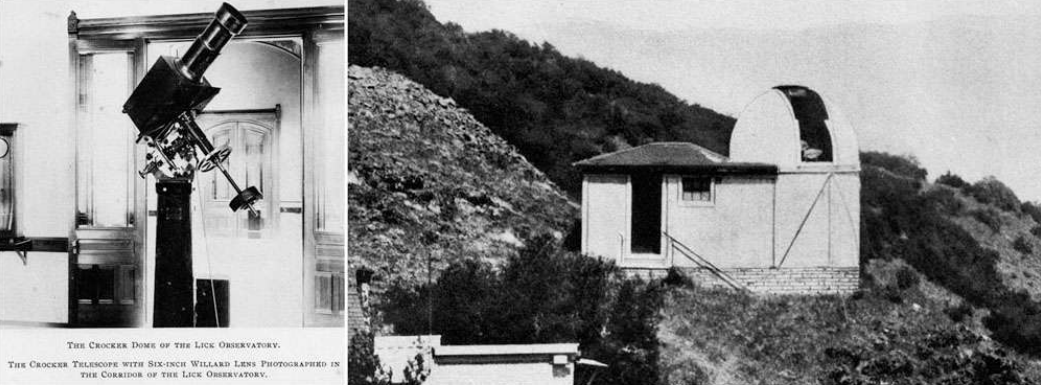

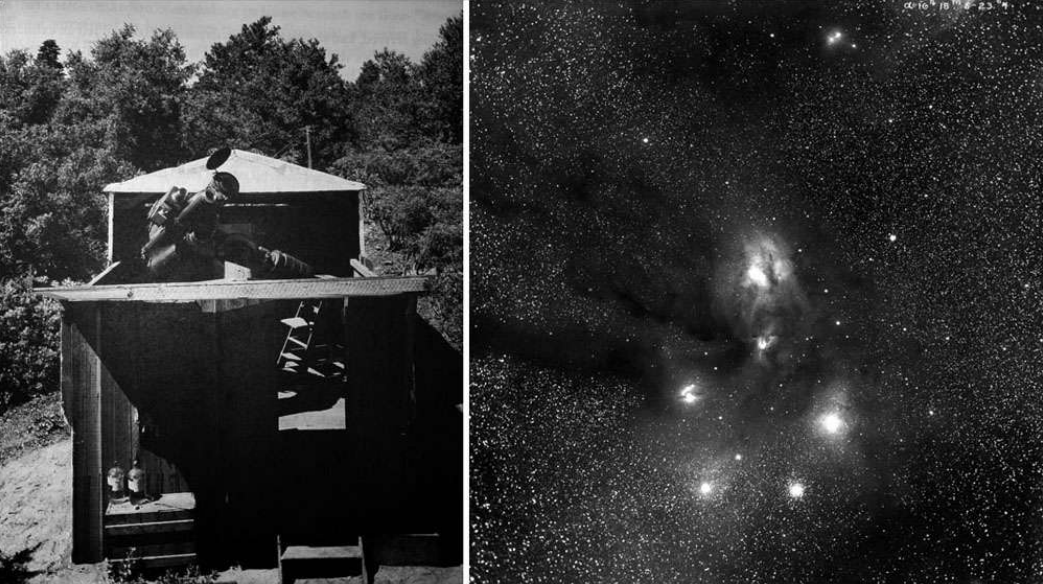

Edward Emerson Barnard publishes *Photographs of the Milky Way and of Comets* in *Publications of the Lick Observatory*, volume 11. These images were taken between 1892 and 1895 using the Crocker telescope.

And here are photographs of the instrument itself:

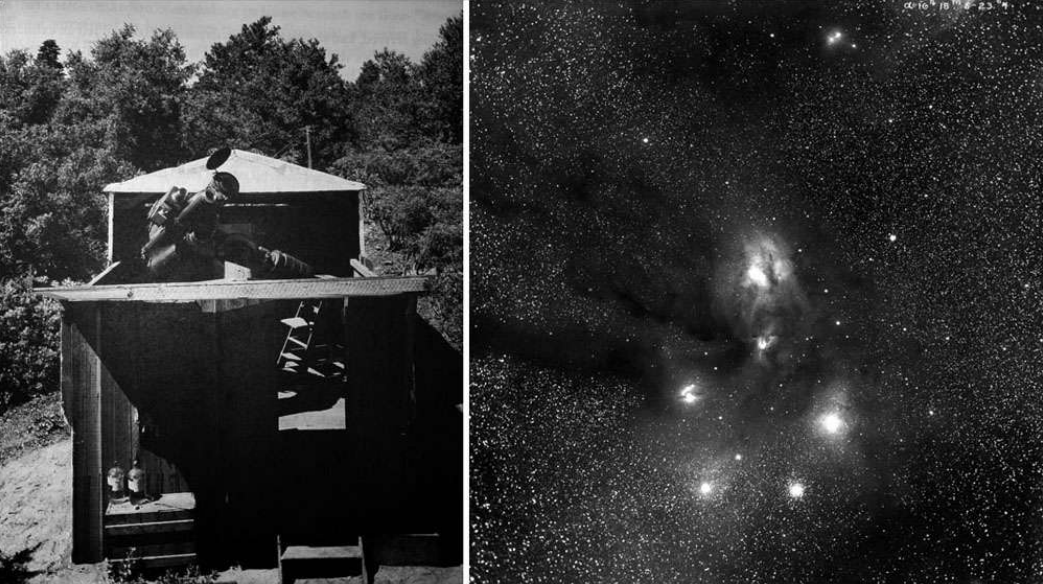

And photos from Mount Wilson Observatory, the Bruce telescope and Barnard himself:

The Milky Way in the constellation Ophiuchus:

Objects named in Barnard’s honor include:

* a lunar crater

* a Martian crater

* a galaxy

* a region on Ganymede

* a mountain in California

* asteroid (907) Rhoda, named after his wife

1924

Edwin Hubble (1889–1953), using the 2.54 meter Hooker telescope, identifies Cepheid variables in the Andromeda Galaxy and measures its distance at 800,000 light years. This discovery transforms our understanding of the universe by proving that galaxies exist beyond the Milky Way.

1927

Publication of *A Photographic Atlas of Selected Regions of the Milky Way*, released four years after Barnard’s death. Most of the atlas photographs (40 out of 50) were taken at Mount Wilson Observatory using the Bruce telescope.

1929

Edwin Hubble discovers that the redshift of galaxies increases with their distance from the Milky Way, now known as Hubble’s Law. This becomes key evidence showing that the universe is expanding.

1929

From 1929 to 1934, French astronomer Marcel de Kerolyr photographs nebulae and galaxies using the 80 cm reflector at the astrophysical station of the Paris Observatory in Haute-Provence.

1930

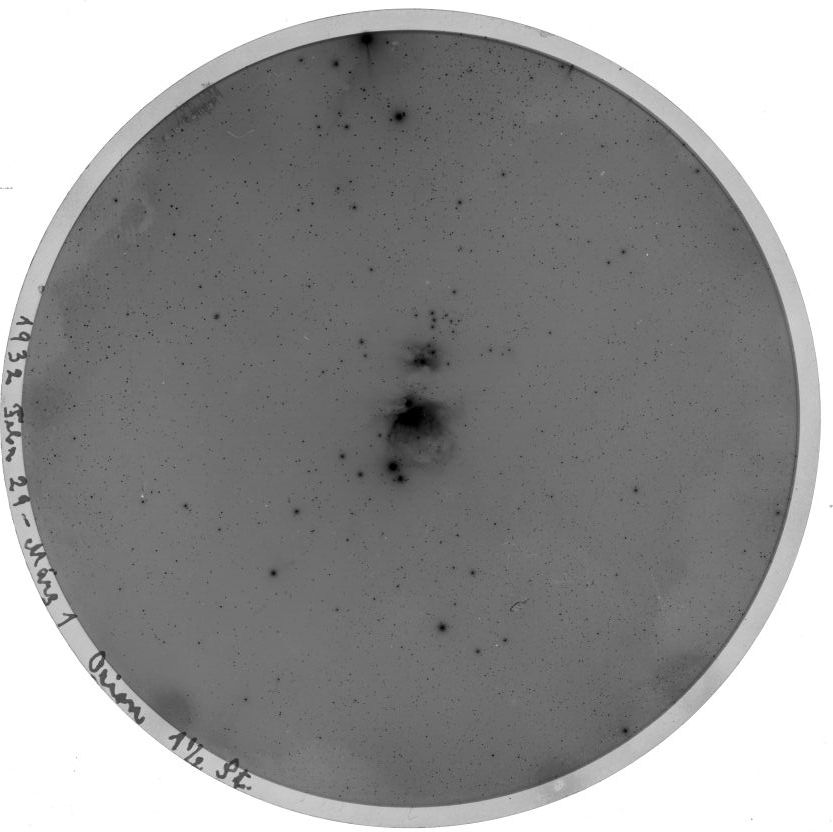

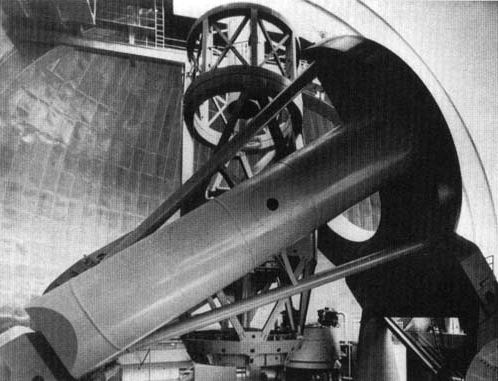

In 1930, the Schmidt telescope design is introduced by Estonian-Swedish optician Bernhard Schmidt, working at the Hamburg Observatory. Schmidt placed an aperture stop at the center of curvature of a spherical mirror, eliminating both coma and astigmatism.

The result was a photographic camera with only one remaining aberration, field curvature, and with remarkable properties: the faster the system, the better the image and the wider the field of view.

In 1946, James Baker adds a convex secondary mirror to the Schmidt camera, producing a flat field. This refined design later evolves into one of the most advanced optical systems we know today: the Schmidt–Cassegrain, which delivers diffraction limited images across a 2 degree field.

Schmidt telescopes become widely used in astrometry for sky surveys. Their main advantage is a very wide field of view, up to 6 degrees. The focal surface is spherical, so instead of correcting field curvature, astronomers simply use curved photographic plates.

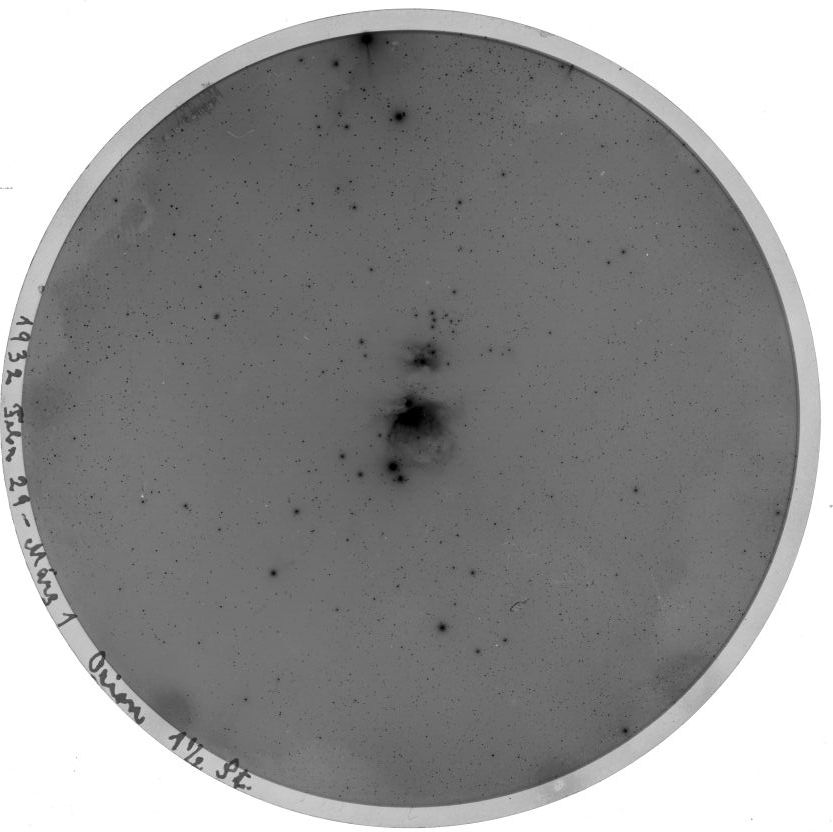

Below is one of the earliest Orion Nebula photographs taken with a Schmidt telescope, on February 1, 1932, with a 90 minute exposure:

1936

1936

Milton Lasell Humason (1891–1972) photographs galaxies at distances of 240 million light years using the Hooker telescope.

The Horsehead Nebula (B33), photographed by Humason with the 200 inch reflector, 1951.

1948

Edwin Hubble uses the new 200 inch (5.08 m) Hale Telescope for the first time at Palomar Observatory, California.

....

And so, almost two hundred years have passed since John Draper captured the first photograph of the Moon. Astrophotography is still a demanding pursuit, yet now accessible to far more people than ever before.

What comes next? We’ll find out in another two hundred years.

If you notice any inaccuracies or incorrect photo identifications, feel free to let me know and I’ll update the text.